More than 100 million young adults are still living in extreme poverty

IFAD Asset Request Portlet

Asset Publisher

More than 100 million young adults are still living in extreme poverty

Estimated reading time: 3 minutes

As global development leaders convene at the Annual Meetings of the World Bank and IMF, messages related to inequality and climate change dominate global headlines and social media, fueled to a large degree by the global youth movement.

In recent years, the concerns and worldviews of young adults have been increasingly occupying center stage in global debates. And they should. The energy, dreams, and demands of the world’s youth (young adults aged 15-24) can be the drivers of massive political, societal and economic shifts. Some of the most important trends expected to shape our global reality during the 21st century—such as the opportunities and challenges of the rapidly increasing cohort of African Youth and the on-going explosion of Asia’s middle class—bring this fact into stark relief.

But what of the youth whose energies will be channeled instead only towards eking out an existence rather than rallying global public opinion? Today, on the International Day for the Eradication of Extreme Poverty, it is important to consider the prospects of the world’s poorest youth.

In collaboration with the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), World Data Lab has pioneered the development of a global poverty model. Based on survey data and national spending distribution forecasts, we’ve developed a method to apply Lorenz curves and regression models to obtain age-specific spending growth rates. Building on these growth rates and national demographic trends, we can calculate country-level poverty numbers by age. The data provides new insights into the landscape of poverty facing youth around the world.

Of the world’s 1.2 billion people aged between 15-24, 104 million—about 9 percent—live on less than $1.90 a day (at 2011 US$ PPP). That’s as much as the total population of Germany and Australia combined. Collectively they represent one-fifth of the world’s poorest people and though their absolute number is expected to fall by about 20 million by 2030, their share of total global extreme poor poverty will stay unchanged. This “structural” nature of youth poverty is driven in part by the relatively sparse opportunities available to harness their productivity, connectivity, and sense of agency. Notably, some 500 million youth live in rural, relatively undeveloped areas where employment opportunities are scarce.

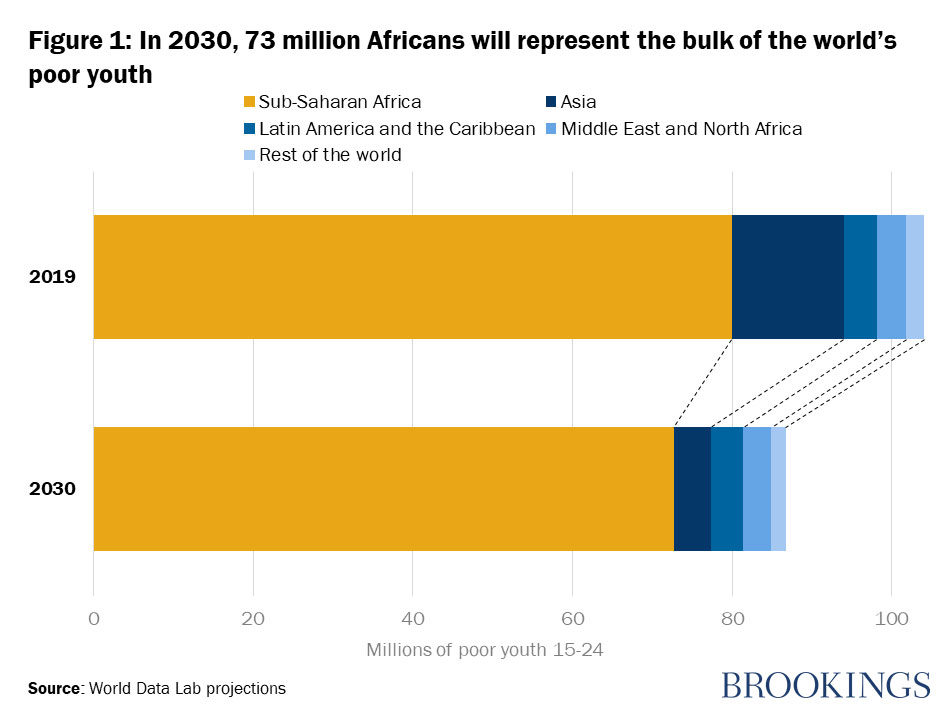

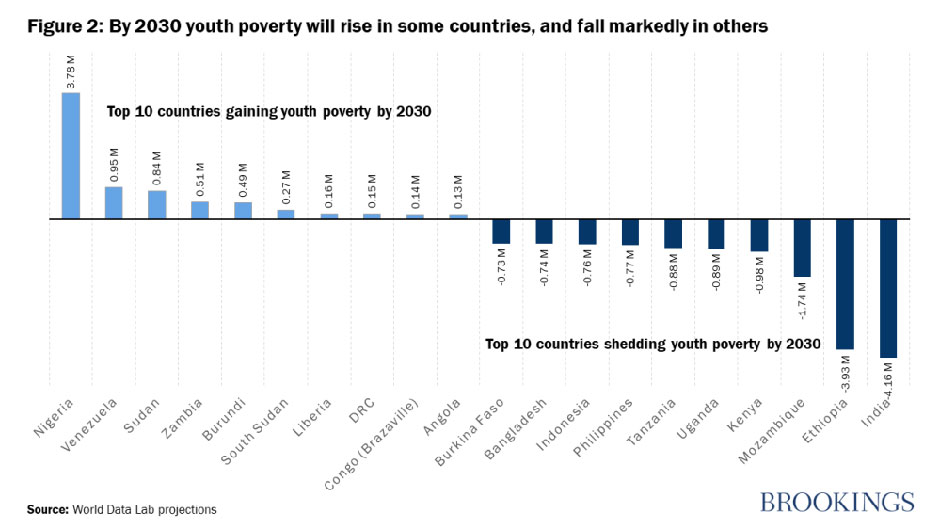

Africa’s 80 million youth living in extreme poverty represent more than three-quarters of the global total (Figure 1). The good news for Africa is that by 2030, their ranks are expected to decline—though only modestly to 73 million. Thanks to improving economic conditions, a handful of African countries are expected to massively reduce the number of poor youth by 2030. Chief among them will be Ethiopia (a reduction of 4 million), Mozambique (2 million), Kenya (1 million), and Uganda (900,000). But some others—Nigeria, Burundi, Sudan, and Zambia—will each have at least half a million poor youth. Considering their sizeable youth populations, sub-Saharan countries have the opportunity of reaping the potential demographic dividend and, consequently, on fostering economic growth. Seizing this opportunity requires effective investments that prioritize rural youth—especially young women—as the majority of youth live in rural areas.

Beyond the opportunities and consequences of Africa’s youth bulge, prospects are markedly varied in other regions. In Asia, the number of youth living in extreme poverty will decline sharply from 14 million to some 5 million people by 2030. India will account for roughly half of this total decline and Indonesia, Philippines, and Bangladesh will each shed some 800,000 poor youth from their total populations. While living in very different economic and political contexts, trends for poor youth in Latin America and the Middle East and North Africa are similar. Each region has one negative outlier—Venezuela and Yemen, respectively—that explains why each region will still have a population of some 4 million extremely poor young people.

The data presented above paint a depressing picture of what is likely to happen should current trends continue. In an effort to change this, some countries are creating opportunities for rural youth populations that aim to strike the right balance between broader interventions for all and youth-specific investments.

Looking at the horizon to 2030, prospects for the world’s poorest youth will also be shaped by two very different economic realities: rapidly increasing urbanization rates, on the one hand, and a persistent legacy of rural poverty in several countries on the other. Converting this changing landscape into wider avenues for unleashing the economic potential of youth is both the problem and the prize for development leaders. Indeed, with only 10 years remaining for policymakers to achieve their Sustainable Development Goal targets, every second counts.

This blog was originally published at brookings.edu

Find out more about creating opportunties for rural youth

Publication date: 21 October 2019