Climate finance keeps carbon where it belongs: underground

IFAD Asset Request Portlet

Asset Publisher

Climate finance keeps carbon where it belongs: underground

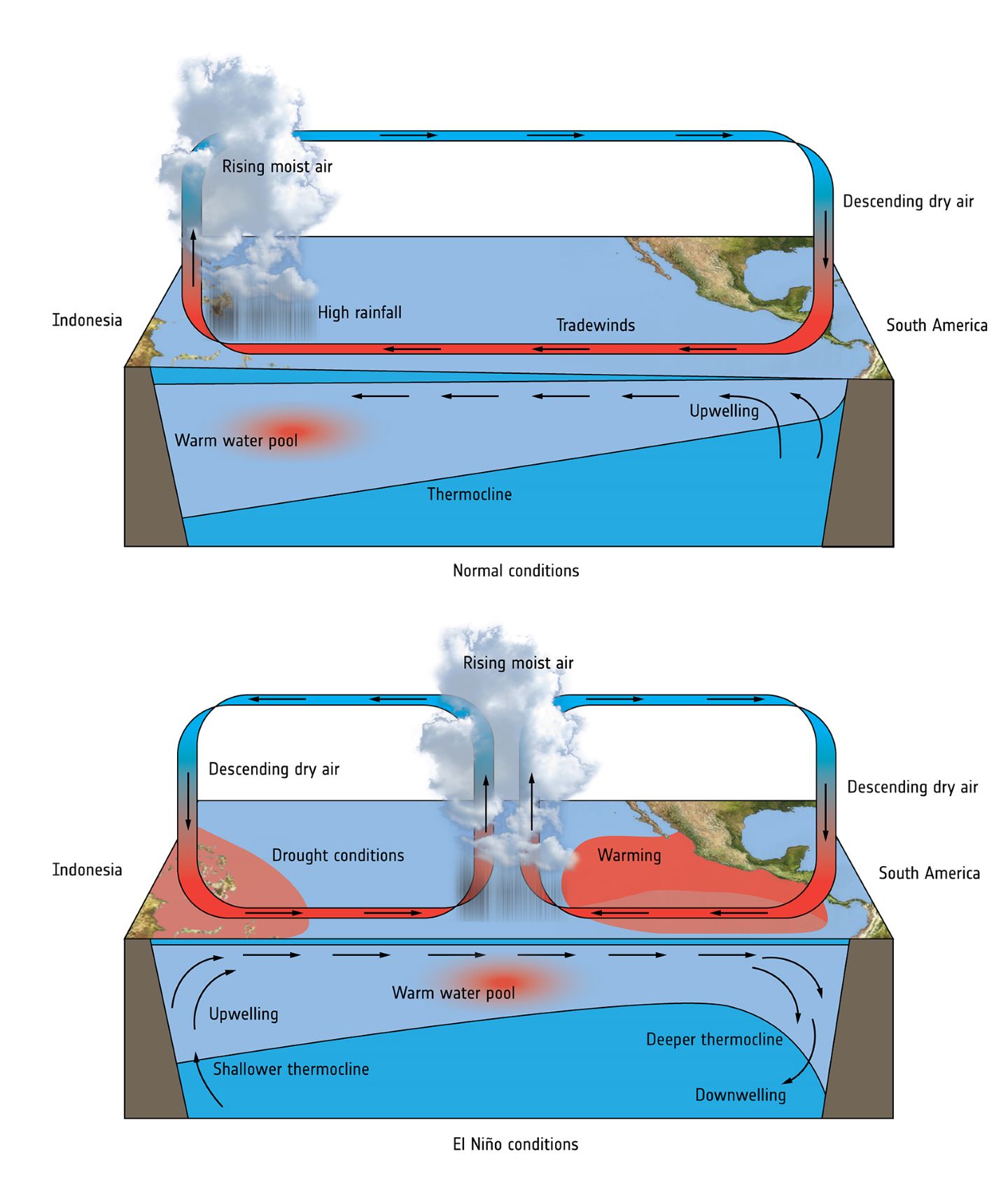

Estimated reading time: 4 minutesFor several months in late 2015, the skies over South-East Asia turned a sickly orange colour. Fuelled by the weather phenomenon known as El Niño, degraded and dried peatlands in Indonesia ignited, and the carbon that they had stored for millennia spewed into the atmosphere, scorching 2.6 million hectares across the island country and causing one of the worst environmental disasters of our century.

As much as 57 gigatons of carbon are stored in Indonesia’s swampy peatlands. As well as accumulating carbon, these biodiversity hotspots are home to endangered species, like the orangutan. Despite their importance, intense logging is making them vulnerable to wildfires.

The 2015 haze event led to an estimated 100,000 excess deaths in Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore, and released more CO2 than the entire carbon dioxide output of the European Union during the same period.

This disastrous outcome could have been avoided if there were proper investments in responding to climate change, otherwise known as climate finance.

What is climate finance?

Climate finance works by mitigating greenhouse gas emissions or by helping communities adapt to the changes that are now known to be inevitable. This funding is essential to prevent the worst-case climate scenarios from happening and to protect the most vulnerable people from a climate breakdown for which they bear the least responsibility.

Climate finance for policy and regulation

In Indonesia, IFAD is channelling more than US$4.7 million in funding from the Global Environment Facility to implement the Sustainable Management of Peatland Ecosystems in Indonesia (SMPEI) initiative.

This initiative helps implement national peatland regulation to identify and restore dried-out wetlands, and a 30-year peatland strategy that is serving as an example for other countries in the region.

Climate finance for communities

But successful government policies rely on people at the frontlines. That’s why climate finance must reach the grassroots level.

In Indonesia, small-scale rural farmers depend on peatlands for their way of life so they are best placed to receive climate finance to conserve these biodiversity hotspots, prevent degradation and keep the carbon underground, where it belongs. In doing so, the SMPEI also improves local living standards so communities can take the lead in conservation.

Project participants develop holistic plans that combine activities to restore degraded peatlands, like blocking drainage canals to return moisture to the water table and thus rewet peatlands, with revitalized livelihoods through activities like farming fish and growing vegetables. The community groups learn from their counterparts in different districts, and collaborate with local companies and government bodies on fire control and water management.

It's showing results.

- Greenhouse gas emissions have been reduced by 19.2 million tons.

- 300,000 hectares of oil palm and forest plantations are managed using improved agricultural practices.

- 22,000 people live in areas where canal blocks are restoring peatlands while providing water for agriculture and aquaculture.

Climate finance on the ground

Aswiri is a coconut and nut farmer whose village, Rambian, has been transformed by the canal blocks installed through SMPEI.

“Before the project, the canal was dry and the land was infertile,” he says. “Therefore, plants like bananas and areca nuts could not grow.” The area was subject to frequent fires during the dry season.

Today, the canal blocks are raising the water table and reviving the peatlands. If fire breaks out, the blocks store water to put it out quickly. They also provide enough water for cultivation. “Coconuts that used to not yield any fruits are now yielding many fruits,” Aswiri says.

Healthy peatlands are not only part of the natural environment for the community in Rambian, they are inextricably linked to flourishing livelihoods. Conserving them makes financial sense.

Climate finance matters

When climate finance reaches the ground, farmers like Aswiri are able to act to protect their livelihoods and their immediate environment, preserving air quality for millions of people across South-East Asia and protecting the planet.

The good news is, climate finance almost doubled between 2011 and 2020, and averaged US$480 billion committed globally per year. The bad news is that it is still lagging behind what is needed: the funds required for adaptation globally are estimated to be 5–10 times higher than international adaptation finance flows. And small-scale farmers receive less than 2 per cent of global climate finance.

Programmes like IFAD’s ASAP+, are helping small-scale rural producers adapt and build resilience to climate change, but more must be done.

Now, with the COVID-19 pandemic, conflict and economic turmoil worldwide, it’s more important than ever that both the public and the private sectors channel climate finance to rural-dwellers and small-scale producers at the sharp end of the climate crisis.

Publication date: 10 November 2022