Land and water are the most essential assets for farmers. Yet, the 500 million smallholder farmers in the developing world, who feed one-third of the world’s population, do not have secure access to those basic resources. As a result, in particular in sub-Saharan Africa, they are unable to make the necessary investments in agriculture, and productivity and production remain low.

Until recently, land and water were often treated as separate issues in country policies. However, access to water cannot be considered independently from secure access to land. Water without guaranteed access to the land where it is found will not be sufficient; and vice versa, land without access to water will be useless for a farmer. The approach to development has to take into consideration the interaction between these two crucial production factors. Without secure land and natural resource rights, smallholder farmers are less willing to invest in sustainable natural resource management measures, thus aggravating environmental problems such as land degradation.

In sub-Saharan Africa, currently some 7 per cent of arable land is irrigated, with a potential of only 20 per cent, leaving 80 per cent of land under rainfed conditions. Here, the condition of soils (texture and structure) is crucial for productive farming, especially their capacity to store nutrients and moisture and release them to plants. Sub-Saharan Africa is the region where 80 per cent of the soils are moisture-stressed, emphasizing the importance of soil rehabilitation as a core factor in our drive to increase productivity and food production.

Our priority in IFAD’s East and Southern Africa division is to look at the overall picture when investing in agriculture – and, within this context, securing land tenure rights, improving the soils and promoting multi-use systems for water, ranging from water for agriculture to domestic water. The trends in climate change reinforce these needs and add an urgency to relevant policy actions and investments. It is only when we implement a comprehensive approach, based on the participation of smallholder farmers and responding to their needs, especially women and youth, that agriculture as a sector will grow and development will be sustainable in the long term, providing income and employment to rural people.

Ides de Willebois

General feature on land and water

Today, smallholder farmers in poor countries feed almost two billion people, and produce most of the food consumed in the developing world. These farmers are typically among the poorest and most neglected in investment terms, yet they play a key role in achieving poverty reduction and food security. Securing their access to both land and water is central to reduce extreme poverty and hunger.

|

||||

|

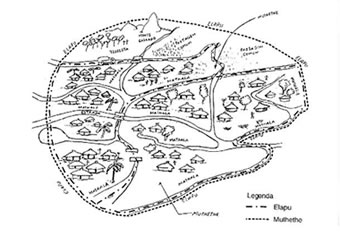

Example of a Community Land Use Map, Mozambique | |||

With the world’s population expected to increase by almost 50 per cent in the next 30 years – from about 6.5 billion to 9.2 billion people – competition for land and water will be further heightened. It is therefore crucial to ensure that smallholders’ needs for land and water are met. For poor smallholder farmers, water and land cannot be treated as separate issues. When they have secure access to both, they invest with confidence in management practices, training, technologies and organizations that enable them to use natural resources wisely. This in turn leads to increased agricultural productivity and improved livelihoods.

Government and development actions focusing only on land or only on water governance changes are unlikely to achieve sustainable impact. “Access to both land and water are extremely important for agriculture to thrive,” says Rudolph Cleveringa, senior technical adviser at IFAD. “However, what is critical is the interaction between the two. They have to work together.”

Over the past ten years, IFAD has supported changes in land and water governance as a way to improve access by poor rural people to these natural resources, and to ensure poverty reduction, increased food security and better livelihoods. This involves working through community-based and civil society organizations and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) to better identify the changes that are needed, and with national and local governments to change policies and legislation. The aim is to empower rural poor people to participate in managing the common property resources on which they depend.

The importance of customary institutions for regulating access to natural resources

IFAD has undertaken a number of case studies to look at how the interaction between land and water governance has an impact on development programmes. It was found that local-level land and water governance structures already exist in some form, but are not systematically recognized at higher institutional levels. If reforms are to improve the livelihoods of poor rural people, their voices and concerns need to be heard and acknowledged as part of the reform process.

In Africa, most land use and access are typically regulated through customary institutions. In recent years there has been growing recognition of the need to integrate customary institutions into decentralized land administration systems. Together, decentralized government and community-based institutions can better address issues of land tenure security and sustainable land management. For instance, in Swaziland, the use of traditional governance structures to support development planning has led to community participation and empowerment that far exceeds initial expectations. Chiefdom Development Plans were originally introduced in the Lower Usuthu Smallholder Irrigation Project (LUSIP) to help communities better understand the impact of infrastructure development and to guide land allocation.

The project’s primary purpose was to convert 6,500 hectares of subsistence agriculture into commercially viable irrigated fields, run and managed by locally formed farmers’ enterprises. In this case, the project looked at existing governance structures to guarantee access to land and water for the local communities involved. “Access to irrigable land was one of the first issues we had to face in the project,” says Louise McDonald, country programme manager at IFAD. Instead, the Chiefdom Development Plans have become a key mechanism for community participation in planning for the overall development of chiefdoms.

In Malawi, a large irrigation project implemented in 2006, the Irrigation, Rural Livelihood and Agricultural Development Project, put in place land tenure agreements before starting to work on developing the planned irrigation schemes (see story below on irrigation in Malawi). “What is important is to secure access to land and natural resources to make sure the use of such resources is sustainable in the long run,” says Harold Liversage, regional land programme manager for East and Southern Africa at IFAD.

IFAD is also supporting the African Union Commission, the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa and the African Development Bank in developing guidelines for land policy formulation and implementation, and is collaborating with the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations in formulating similar global guidelines for good land and natural resource governance.

Gender aspects

Gender is also an important aspect when dealing with land and water governance. Women are the main food producers. For example, they account for half to three-quarters of all the food produced by smallholders in most of sub-Saharan Africa. Therefore, it is rural women farmers who are the key to achieving food security, better nutrition and higher living standards. However, in some countries women have difficulties accessing natural resources, land in particular, because of traditional inheritance systems that may favour the male line. How to reach women more effectively in communities where they are the key food producers is a critical question. For example, the Participatory Small-scale Irrigation Development Programme, started in 2008 in Ethiopia, encourages women to join the decision-making bodies of water users' associations, set up to manage irrigation schemes. “Gender is a strong element of land and water management, and it needs more attention,” says Audrey Nepveu, technical adviser on agricultural water management at IFAD. “In the majority of cases, women are feeding the family.

They need secure access to both land and water, water for agriculture and water for domestic use.”

In particular, women need easier access to domestic water to free up time for other productive tasks. In many rural communities, women still spend a great amount of time fetching drinking water from the nearest well, which can be located kilometres away.

“Providing drinking water sources closer to their home would enable them to have more time to work the land. We also need to invest more in small technologies to promote so-called backyard gardening,” Nepveu added. Currently, domestic water investments represent about 35 per cent of the East and Southern Africa division’s water portfolio. These investments benefit mainly women, and are guided by IFAD’s demand-driven approach whereby poor rural people define their own needs.

Natural resources degradation

Degradation of natural resources is another issue in African countries and is often a consequence of undefined ownership of the land. Many IFAD-supported projects in the region try to tackle the issue of degradation at the same time that they are developing agriculture infrastructure. In Lesotho, for example, the Sustainable Agriculture and Natural Resource Development Programme looked at ways of reversing land degradation due to poor land management (see story below on fighting land degradation in Lesotho).

Similarly, in Ethiopia an estimated two billion tonnes of fertile soil are lost annually because of land degradation. The IFAD-supported Community-based Integrated Natural Resources Management Project, in the Lake Tana area, aims to improve farmers’ land tenure security and thus encourage them to invest in land improvements. The project’s objectives are to enhance the access of poor rural people to natural resources such as land and water, and to improved technologies for agricultural production and sustainable land management.

However, as much as land issues are important, the management of water sources for agriculture remains crucial because agriculture accounts for more than 80 per cent of water use. In the East and Southern Africa region, at the end of 2009, 44 out of the 51 ongoing loan projects in 16 countries included water-related activities, ranging from managing resources to allocating them to various uses, such as domestic, agriculture and the environment. Primary investment went to the agriculture sector, with 51 per cent of projects investing in irrigation, 41 per cent in rainfed water management, 31 per cent in water for livestock and 14 per cent for inland fisheries. Agro-processing, adding value to production (for example, washing of produce before packaging) also represented a significant water investment in the water portfolio. Improving management of agricultural water therefore remains a priority for IFAD’s East and Southern Africa division.

Building a strong water network

In 2006, IFAD launched the Improved Management of Agricultural Water in East and Southern Africa project (IMAWESA) to enhance the development impact of investments in smallholder agricultural water management (AWM) in the region. IMAWESA, which just completed its first phase, has created a useful network of water management specialists and water users dedicated to generating, documenting, packaging and sharing lessons and successful practices for implementing AWM. An external evaluation, completed in early 2009, showed that IMAWESA has built a reliable network of regional professionals who can provide solutions to AWM problems and whose expertise can be used for technical assistance, training and applied research.

- IFAD-supported projects in the region continue to request support from IMAWESA. Among others, the Support Project for the Strategic Plan for the Transformation of Agriculture in Rwanda requested advice on technologies for hillside and upland irrigation as well as water management in watershed planning.

- IMAWESA is now entering its second phase, which will be managed by the International Water Management Institute (IWMI). The project intends to establish the premier network for finding all knowledge on AWM, as well as for facilitating capacity building of stakeholders to undertake AWM, and assist them to turn knowledge into action, with technical support provided on demand. IMAWESA’s knowledge-sharing and networking activities will seek to reach all 21 countries covered by IFAD’s East and Southern Africa division. Furthermore, it will work closely with the region’s other networks, such as IFADAfrica.

For more information, contact:

Harold Liversage, Regional Land Programme Manager, ESA Division, IFAD

[email protected]

Integrating land, water and natural resources governance

|

||||

|

Working newly irrigated land in Malawi | |||

It is estimated that less than 10 per cent of all land in Africa is registered under statutory systems. Most farm land in Africa is officially owned by national states; however, it is owned de facto by local rural communities under diverse customary tenure systems which balance individual or familial rights with group or community rights. The past decade or so has seen greater legal recognition of customary tenure systems and an associated integration of these systems with decentralized state land administration systems, resulting in accelerated land registration in certain countries (for example, Madagascar and Rwanda).

Water and other natural resources such as trees, natural vegetation, medicinal plants and fish are also typically managed under diverse customary tenure systems; however, statutory regulation of water and forests is perhaps more developed. Typically individual or familial rights are held over residential plots and crop lands, and group or community rights are assigned to grazing lands and forests. Hence, sustainable land management requires recognition of a combination of local by-laws, rules and regulations. Soil and water conservation and forestation measures are undertaken on both familial and communal land. Fodder can be grown on familial land or communal land, but improvements to range and grazing lands are typically made on communal land. Introducing irrigation can have a major impact on land rights. The increase in land potential and value can result in more vulnerable people losing access to land.

Most IFAD-funded projects and programmes in the East and Southern Africa region that take up irrigation and sustainable land management are addressing issues of land tenure security and equitable access, often coming up with innovative solutions. For example:

- The Lower Usuthu Smallholder Irrigation Project in Swaziland, the Kirehe Community-based Watershed Management Project in Rwanda and the Irrigation, Rural Livelihood and Agricultural Development Project in Malawi are all developing approaches to better document land and water rights and ensure safeguards for equitable land access with the introduction of irrigation. In Rwanda, procedures are being developed to transfer land and water rights in government-owned productive marshlands through Irrigation Management Transfer agreements. Land parcels are being demarcated and assigned to individual members. The project is also supporting the systematic registration of family land. The project in Rwanda is also exploring the option of linking carbon sequestration to forestation on public and family-owned land. In the case of family-owned land, registration of the land will reduce ownership disputes and improve farmers’ ability to access credit to invest in trees and other productive activities. In the case of public land, management responsibility for demarcated areas could be granted to forest or wood-lot associations.

- In Madagascar, all recent projects have supported the registration of customary lands through local land offices, called guichets fonciers. Broader project objectives include improvements to land and natural resource use planning.

- In Lesotho, the Sustainable Agriculture and Natural Resource Development Programme is supporting the establishment of grazing associations and the development of land management by-laws and regulations for demarcated communal grazing areas.

- In Tanzania, the Sustainable Rangeland Management Project, which is being implemented under the Agricultural Sector Development Programme – Livestock, is supporting the improvement of village land use management plans as a basis for better managing land and water resources and mitigating disputes between crop and livestock farmers.

- In Mozambique, the Artisanal Fisheries Promotion Project (PROPESCA) is exploring options for strengthening the mapping of fishing and other resources rights of artisanal fishing communities.

For more information, contact:

Harold Liversage, Regional Land Programme Manager, ESA Division, IFAD

[email protected]

Malawi: Irrigation project highlights land tenure issues

|

||||

|

IFAD/D.Magada 2010 - Canal at Likangala ex-government irrigation scheme | |||

The government of Malawi has set irrigation as one of its top priorities. Water is of great concern in Malawi, particularly for agriculture. Most farmers have to rely on weather conditions and unpredictable rainfall for their crops. Irrigation is scarcely developed and the few large-scale government irrigation schemes have been neglected and fallen into disrepair. As a result, agricultural productivity is low and production erratic.

In 2006, an irrigation project was launched, jointly supported by IFAD and the World Bank. The objective of the Irrigation, Rural Livelihood and Agricultural Development Project is to raise agricultural productivity and net incomes of poor rural households by providing an integrated package of support covering irrigation, agricultural/irrigation advisory services, and marketing and post-harvest assets and services. However, because irrigation is closely linked to land tenure, the project had to address land tenure issues before starting to work on the irrigation schemes. In particular, it focused on land contracts to allow ownership of the irrigation schemes to be transferred from the government to the local communities.

|

||||

|

IFAD/D.Magada 2010 - Canal at Windu small scale irrigation scheme | |||

One component of the project is to rehabilitate four disused government schemes covering 1,800 hectares of fields to be irrigated, and consequently transfer their ownership to the communities who will benefit. This is achieved by establishing water users’ associations (WUA) at the same time that the schemes are being rehabilitated. However, before the WUAs could be formed, much time had to be spent resolving land tenure issues regarding the land where the schemes are located. It was agreed that the Government of Malawi would grant long-term leases to the WUAs and facilitate the subsequent sub-leasing by the WUAs to their members. So far, land lease agreements between the Ministry of Lands and WUAs have been drafted for all of the government schemes. However, as the WUAs have not yet been registered, lease agreement offers, except in one case, have not yet been made. “A great amount of the project’s resources are currently dedicated to building farmers’ capacity to set up and manage their WUA,” says Dickxie Verson Kampani, coordinator of the project in Lilongwe.

The communities involved are fully participating in the construction work and are being trained to manage the schemes through their own WUA. “As we will own the irrigation scheme, we are being trained to run and manage it through the association. We’re getting leadership training, conflict management training, as well as technical training,” explains Rose Timbo, vice-chairperson of the WUA in Likangala. The canals are under construction, and part of the scheme should become operational by the end of 2010. The region produces mainly rice and maize.

The project is being implemented in 11 districts of Malawi in the Northern, Central and Southern regions. Like many other IFAD-supported projects, it is demand-driven and based on full participation of the communities. Total investment amounts to US $52 million for the six-year duration of the project (2006-2012), of which IFAD is contributing US$ 8 million.

|

||||

|

IFAD/D.Magada 2010 - Construction at the Windu small scale irrigation scheme | |||

Allocations of land parcels to members are expected to be regulated by the WUA committees once they are in place. Currently WUAs intend to allocate parcels on an annual basis, but this could undermine members’ land tenure security and willingness to invest in land and farming. However, it is expected that farmers will retain the same parcels. To ensure equitable benefit sharing, minimum and maximum limits on the number of parcels that members can access are set by interim WUAs. Typically plots are about 0.1 hectares. Limits to the number of plots that a member can access vary between schemes. For instance, in Likangala, farmers can be allocated up to four parcels, compared to other schemes where the number can range between 4 and 12 parcels.

In addition to the government schemes, the project supports the development of new small-scale gravity schemes of 10 to 50 hectares each, for a total of around 500 hectares, as well as mini-scale schemes of 2 to 10 hectares for a total of 300 hectares. While no specific activities were identified during the design of the project with regard to land tenure security issues, the project is supporting the documentation of land-sharing arrangements in small-scale irrigation schemes on customary land.

|

||||

|

IFAD/D.Magada 2010 - Rose Timbo chairperson of the Likangala water users association | |||

Most small-scale and mini-scale schemes are being established on land already belonging to one or more owners, depending on the size of the land. In Malawi, most of the land is under customary ownership, and is allocated mainly through traditional authorities. Families are being allocated land in perpetuity provided they continue to use it. In the south and centre of the country, customary systems are matrilineal while in the north they are patrilineal.

As with the government schemes, land parcels are about 0.1 hectares. In the mini-schemes land parcels may be smaller and in some cases not divided but instead operated as communal gardens. Since the project was launched, another 200 mini- irrigation schemes have been developed on a demand-driven basis in addition to the schemes originally planned. In those schemes, farmers tend to already be owners of a plot of land. In total, the project has developed additional mini-irrigation schemes on 1,496 hectares. The schemes are benefiting more than 20,000 farm households. The challenge now will be to ensure that these schemes are sustainable and that farmers are satisfied with the system and receive sufficient management training to develop crops.

New land policy in Malawi

Since 1994 and the introduction of multi-party democracy, the country has developed a new Land Policy which will result in a new Land Act to be approved by Parliament by the end of the year. Among other things, the Act proposes the vesting of all land in the people of Malawi and stipulates that all citizens who need land for livelihoods shall be given access. It will aim to improve tenure security by clarifying and strengthening customary land rights and by formalizing the role of traditional authorities in the administration of customary land. The Act will provide for the registration of customary land and customary land transactions, and will seek to bring about a more equitable distribution of land by resettling people from crowded to less densely settled areas. Emphasis is placed on the decentralization of land administration. Spousal rights will be equally recognized - husbands and wives will be treated as separate persons in land registration and transactions. Foreigners may not buy private land and can only be granted leases of up to 50 years, unless special permission is granted.

For more information, contact:

Miriam Okong’o, Country Programme Manager, ESA Division, IFAD

[email protected]

Starting the fight against land degradation: A war Lesotho cannot afford to lose?

|

||||

|

IFAD/Barry Mann 2010 - Panoramic View of the Maliepetsane Catchment at Ha Mosala. | |||

|

||||

| IFAD/Barry Mann 2010 - Chief Mamaebana, Liako Moholobela | ||||

Travelling through the Lesotho countryside you can’t help but notice the severe erosion that scars the landscape. Vast areas of once fertile fields have been reduced to an unproductive wasteland as a result of poor land management over many years. Realizing that something had to be done to protect their future, the Chief and villagers of Ha Mosala, Mafeteng District, have started to reverse the effects of the land degradation in their area, with the support of an IFAD-funded programme, the Sustainable Agriculture and Natural Resource Development Programme (SANReMP).

Chief Mamaebana, Liako Moholobela has lived in the area around Ha Mosala for many years, and as she stood overlooking the valley she recalled, “The dongas (gullies created by heavy flows of running water eroding the soil, often a consequence of deforestation or over-grazing, as the soil is more easily dislodged) first started developing on the land around Ha Mosala in 1946. After 60 more years of overgrazing and erosion, the land was bare, covered by dongas, and in many places we were unable to farm it any longer. In 2007 we realized that something had to be done to protect our community.”

In 2007 the Chief and the community started working with SANReMP and the Government of Lesotho to try and reverse the effects of land degradation – not an easy task in a country which is open, free of fences and where herd boys graze their animals without restriction.

|

||||

|

||||

|

IFAD/Barry Mann 2010 - Evidence of the stone walls being used to stabilize the soil within the dongas at Ha Mosala. | |||

The Mosala Community Action Plan was drawn up, and an initial area covering 4.5 hectares was identified within the Maliepetsane catchment to start the regeneration work. The Chief declared that the land should not be farmed and that animals should not graze there. Stone walls were built across the dongas to help stop the flow of water and trap silt behind them, while the steep donga sides were reshaped to allow them to be reseeded. Eucalyptus, acacia and poplar trees were also planted to help stabilize the soil.

SANReMP provided the funds for the project inputs, which have consisted of enough grass seed to reseed 4.5 hectares and the 16,000 tree seedlings, which have been planted. Today, walking through the regenerated area, the success of the project can be seen all around. Trees and grasses are well established, and soil that would have previously just washed away into the river has filled up the gullies behind the stone walls. These areas have in turn been re-seeded with some of the tree seedlings and grasses. Kamehelo Ramoshabe, the area grazing control officer, pointed out that no grazing had taken place in the area. He explained, “The project has the support of the Chief and community, and they have managed to keep farmers and herd boys from grazing this area of land. Educating the community is a big part of the project, ensuring that they are aware that they mustn’t graze their animals in this area.”

|

||||

|

IFAD/Barry Mann 2010 - Established Eragrostis curvula planted as part of the programme | |||

Regeneration of the land in this particular area is only the beginning. The Chief pointed across the valley and said, “Everyone in the community can see the results in this area for themselves. It has been such a success that we want to expand the regeneration programme to other areas in the valley.” Local farmer Thabo Ntsohi added, “This is a sustainable scheme. We are now more selective about the areas where we graze our animals, but the plans are to start cutting the grass in this regenerated area to make fodder for our animals. Expanding the areas of regenerated land will provide benefits to all those in the community who have animals.”

|

||||

|

IFAD/Barry Mann 2010 - Newly planted Eragrostis curvula and evidence of no grazing in the area | |||

The community also plans to use the trees, once they are more mature, to provide a source of firewood, which will be sold to provide a much-needed additional source of income.

Some of this income will be used to help fund the regeneration of other areas of land.

Having seen the success of the project, several entrepreneurial villagers have also started tree nurseries this year to produce tree seedlings, which they hope to sell for use in other similar regeneration projects.

The success of the scheme at Ha Mosala, backed by SANReMP, has proved that it is possible to reverse the devastating effects of land degradation. The villagers are rightly proud that the Lesotho Ministry of Forestry and Land Reclamation has recently chosen the site to demonstrate and celebrate one important way in which land degradation can be addressed. The future for the villagers is starting to look up.

For more information, contact:

Fumiko Nakai, Country Programme Manager, ESA Division, IFAD

[email protected]

An ancient form of water management helps farmers in Eritrea cope with water scarcity

Water is precious in Eritrea, where farmers have to cope with droughts and crop failures. With support from the government and an IFAD-funded project, farmers and herders are expanding spate irrigation, an ancient form of water management. By harnessing floodwaters and collecting run-off, farmers can provide enough water for the crop season. Now some farmers can obtain yields that are six times what they used to be.

|

||||

|

Photo credit: Roxanna Samii Eritrean farmers | |||

Water scarcity is one of the many challenges that farmers face in Eritrea. The country has two perennial river systems, the Setit River, which forms the country’s border with Ethiopia and drains into the Nile basin, and the Gash Barka system, which collects the run-off water from the highlands. All other rivers in the country are seasonal and carry water only after rainfall, which means that they are dry most of the year. The country has limited sources of fresh surface water, and although groundwater can be tapped, quality may be poor.

The average annual rainfall is approximately 380 mm. Rainfall is usually torrential — of high intensity and short duration — and varies greatly from year to year.

The Gash Barka region in the south-west of Eritrea has a harsh climate, with rainfall that is limited and unreliable. The region shares its western border with Sudan and its southern border with Ethiopia. It has a surface area of 37,000 km2, which constitutes one-third of Eritrea's land area, and a population of 567,000. Gash Barka was severely affected by the 1998–2000 border conflict with Ethiopia. Eight years after the conflict, carcasses of tanks and other military hardware can still be found there.

|

||||

|

Photo credit: Roxanna Samii Carcasses of tanks | |||

Every three to five years, droughts cause partial or complete crop failure in the region. When crops fail, farmers and herders sell their livestock and other assets as a survival strategy.

The IFAD-funded Gash Barka Livestock and Agricultural Development Project introduced improvements in grazing and farming. The project also supports infrastructure works, such as spate irrigation systems. Efforts to develop and improve the systems include harnessing run-off and diverting rivers and small streams, improving hafirs (ponds) to collect water for livestock, and water harvesting.

Spate irrigation – an ancient form of water management – is one of the most viable ways of supporting the livelihoods of economically marginalized farmers. It is different from conventional perennial irrigation and is used in areas prone to unpredictable and destructive floods, particularly in arid and semi-arid areas.

How does spate irrigation work?

Spate irrigation is a resource system, harnessing floodwater or ephemeral streams and diverting the water to agricultural fields through earthen or concrete canals. It is a pre-planting system, in which the crop season follows the flood season. In the Gash Barka and Debub regions, major floods occur between June and September, and the main crop season is between September and February.

|

||||

|

Photo credit: Roxanna Samii Spate irrigation channels | |||

Spate irrigation systems are usually established in the plains around mountainous or hilly areas in order to collect run-off, allowing low-lying fields to store moisture for crops during the crop season.

"Farmers can start planting their crops only after irrigation has taken place," explains Efrem Tekle, crop specialist in the Ministry of Agriculture. "Since the timing, volume and number of floods are highly unpredictable, this type of agriculture is prone to risk. Farmers need to cooperate closely with one another to manage the distribution of flood flows and also to manage and maintain the spate irrigation system."

The Government of Eritrea, the Ministry of Agriculture and the IFAD-funded Gash Barka Livestock and Agricultural Development project have joined to finance the construction of spate irrigation systems in the Gash Barka region.

The Hashenkit River Diversion project is strategically situated to serve 14 villages and a total of 1,300 families, of which 20 per cent are households headed by women.

The region’s farmers traditionally plant sorghum. Sorghum is the fifth most important cereal crop in Eritrea, after wheat, rice, maize and barley, but it is the leading crop in Gash Barka. It is used for food, feed, fodder and fuel.

"We know that improved sorghum has better quality and high production value. But, given our reality of water scarcity, we prefer to plant traditional sorghum because it needs less water," says Adam Humed, a farmer.

|

||||

|

Photo credit: Roxanna Samii Adam Humed, an Eritrean farmer | |||

"Before the spate irrigation system we engaged in rainfed farming, and our yield never exceeded 5 quintals [500 kg] per hectare," Humed explains. "Spate irrigation has increased our yield up to six times, which means 20-30 quintals [2,000–3,000 kg] per hectare. As a result we are able to feed our children and buy new livestock."

Like all infrastructure, spate irrigation works need to be maintained. It is necessary for farmers' organizations to establish a good relationship with the local government so they can jointly administer and maintain the infrastructure. To administer the spate system the farmers also need to collaborate and agree on equitable water distribution.

"We will be meeting with the local government to propose that if they help us with levelling, removing the silage and improving the channels, we will take charge of maintaining the spate," says Humed.

Looming shadow of drought

"We face many challenges. One of them is drought, which has a three- to five-year cycle", says Humed. "This year we had only 10 mm of rain, which means a decrease in food production and increased vulnerability."

"The Gash Barka region has approximately 3.5 million head of livestock," Humed explains. "In this community, approximately half of the households own livestock, and on average each household has from six to seven head of livestock."

|

||||

|

Photo credit: Roxanna Samii Eritrean village | |||

The pastoralists consider their livestock to be a valuable source of income. "Livestock is a source of money, because we can sell the animals when faced with hard times," says Humed. "We have learned to put aside 10 per cent of our income during good times, in a community saving scheme. As a result, today we have 240,000 nafka (US$ 16,000) in our saving account, which we use in times of crisis."

The Ministry of Agriculture and the IFAD-funded project are conducting capacity-building and awareness-building campaigns to demonstrate the benefits of good storage mechanisms as an alternative way of coping with crises such as droughts.

"The awareness campaign is helping pastoralists and farmers understand that the price of livestock will decrease substantially during drought because there is an over-supply," says Yordanos Tesfamarian, senior economist in the Ministry of Agriculture.

"Extension workers are imparting knowledge to the farmers about how to take advantage of a bumper year by investing in proper storage, so that when drought hits, the farmers have food and also the possibility of selling their surplus at higher prices."

"By working together with the farmers to identify their needs and aspirations and by involving them in decision-making processes, we are building their capacities and those of their institutions so they can advocate for themselves," explains Abla Benhammouche, IFAD country programme manager for Eritrea.

"This is how we are ensuring full ownership and sustainability."

For more information, contact:

Abla Benhammouche, Country Programme Manager, ESA Division, IFAD

[email protected]

Loans approved by the September 2010 Executive Board

- Kenya

Programme for Rural Outreach of Financial Innovations and Technologies, US$ 29.3 million

- Uganda

Agricultural Technology and Agribusiness Advisory Services Project,

US$ 14 million

- Zambia

Smallholder Agribusiness Promotion Programme – supplementary grant,

US$ 1 million

Grants and loans to be approved by the December 2010 Executive Board

Country loans

- Tanzania : Marketing Infrastructure, Value Addition and Rural Finance Support Programme (MIVARF), US$ 91 million

- Mozambique: Artisanal Fisheries Promotion Project (ProPesca), US$ 21 million

- Botswana : Agricultural Support Services Programme (ASSP), US$ 4 million

Regional grants

Regional Programme for Rural Development Training (PROCASUR): Learning Routes: A Knowledge Management and Capacity Building Tool for Rural Development in East and Southern Africa, US$ 1.5 million

Institute for People, Innovation and Change in Organizations (PICO): Network for Enhanced Market Access for Smallholders (NEMAS) in East and Southern Africa, US$ 1.5 million

Uganda

All four IFAD loans to Uganda have now been approved. Supplementary loans to the Community Agriculture Infrastructure Improvement Programme (CAIIP) for US$17 million and the District Livelihoods Support Programme (DLSP) for US$18 million were approved in September 2009. The second phase of the Vegetable Oil Development Project (VODP2) was approved in April this year for an amount of US$52 million, and the US$14 million loan to the Agricultural Technology and Agribusiness Advisory Services Project (ATAAS) was approved at the Executive Board in September 2010. These have been through all internal government administrative and parliamentary processes and were approved by Parliament in mid-October.

Seven supervision and implementation support missions for four IFAD-supervised projects were carried out by 31 October 2010; the last mission scheduled will be carried out in mid-December 2010.

Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Programme (CAADP) The agreement was signed by 15 donors in March 2010. The World Bank led the first CAADP review mission in September this year and has made concrete recommendations to strengthen the Government of Uganda’s implementation of its CAADP Agenda.

The Agri-Business Forum took place in Kampala on 4-6 October 2010, during which the Director of the East and Southern Africa division made a presentation on Innovative Financial Solutions.

Eritrea

- Implementation Support/Supervision Mission to the Post-Crisis Rural Recovery and Development Programme (PCRRDP) and the Gash Barka Livestock and Agricultural Development Project (GBLADP) took place from 27 September to 14 October.

- The start-up mission and workshop to the Fisheries Development Project (FDP) took place from 4 to 8 October.

Lesotho

- The Design Mission to the Smallholder Agriculture Development Programme is scheduled to take place from 22 November to 3 December. This will be a joint design mission with the World Bank.

- The Implementation Support Mission to the Rural Financial Intermediation Programme is scheduled to take place from 29 November to 10 December.

Mauritius

- The Implementation Support/Supervision Mission to the Rural Diversification Programme (RDP) and Marine and Agricultural Resources Support (MARS) Programme are scheduled to take place from 20 November to 16 December.

Mozambique

- The joint IFAD-AfDB Supervision Mission to the Rural Finance Support Programme took place from 20 September to 1 October.

- A Supervision Mission for the Programme to Support the Food Production Action Plan (PRO-PAPA), financed by the European Commission Food Facility, will be carried out between 22 November and 4 December.

- The Supervision Mission for the National Programme for Agricultural Extension is scheduled to take place from 22 November to 4 December.

- The Supervision Mission to the Rural Finance Support Programme (RFSP) took place from 21 September to 1 October.

- The Supervision Mission to the Agricultural Support Programme (ASP/PRONEA) is scheduled to take place from 22 November to 3 December.

Kenya

- The East and Southern Africa division Regional Financial Management Workshop took place in Nairobi from 20 to 22 September. The three principal subjects of the Workshop were loan administration, procurement, and accounting & audit.

Mozambique

- The COSOP Final Design Workshop took place from 4 to 8 October. The purpose of the workshop was to collect and discuss the results of the local consultations with smallholder producers (farmers and fishers), allow local stakeholders to share their views on the draft COSOP and discuss ideas about future investment for new IFAD loans and grants during 2011-2015.

- The East and Southern Africa Regional Implementation Workshop is scheduled to take place in Maputo from 15 to 19 November. The theme of the workshop this year will be “Sustainable Management of Land and Water to Improve Agricultural Productivity”.

- The workshop on "Opportunities and Challenges for Securing Women’s Land Rights" is scheduled to take place on 19 November.

- A Consultation Meeting with producers' organizations on the IFAD Mozambique COSOP 2011-15 took place on 4 October.

- A seminar with the enlarged country programme team on the IFAD Mozambique COSOP 2011-15 took place on 5 October.

- The Women's Land Rights Workshop (organized by IFAD) will take place on 19 November.

Appointments and staff movements

- Mr Aimable Ntukanyagwe was recruited as Country Programme Officer for Rwanda.

- Ms Adriane Del Torto was appointed as Programme Assistant for Kenya, Burundi and Comoros.

- Mr Daniel Maina was appointed through UNON as Regional Financial Analyst and is based in the Nairobi office.

- Ms Elisabeth Ssendiwala Nyambura was appointed through UNON as Regional Gender Coordinator for the East and Southern African division and is based in the Nairobi office.

- Ms Agnes Kiragu was appointed through UNON as Administrative Assistant and is based in the Nairobi office.

- Ms Hélène Ní Choncheanainn was recruited as Programme Assistant to the Knowledge Management Officer.

Congratulations and welcome to Aimable, Adriane, Daniel, Elizabeth, Agnes and Hélène.