Joint message from the Directors

|

||||

|

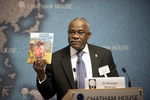

Kanayo F. Nwanze at the Rural Poverty Report 2011 launch, Chatham house, London. | |||

Despite massive progress in reducing poverty in some parts of the world over the past couple of decades, there are still about 1.4 billion people living on less than US$1.25 a day, and close to 1 billion people suffering from hunger. More than two thirds of the world’s very poor people are rural; sub-Saharan Africa has the highest incidence of rural poverty, and is the one region where poverty levels haven’t declined over the past decade. For sub-Saharan Africa, the key to alleviate rural poverty is enhancing agricultural productivity, since agriculture is still the dominant sector in most countries. This means not only producing the food required, but also ensuring employment and more secure income generation for the majority of the population. To this end, investment in agriculture and the rural non-farm economy needs to be increased to levels that will allow sustainable improvements in the rural economy. In particular, the infrastructure in many sub-Saharan African countries is not adequate, preventing farmers from reaching markets easily. As a result, they remain in a cycle whereby they grow their own food for subsistence, unable to develop more commercial activities. Even if new technologies such as fast internet and “smart phones” are slowly improving the situation, there are still many hurdles to overcome, including market access and governance.

As an international organization focused on poor rural people, IFAD is piloting new approaches and ways of working, paying particular attention to the whole value-chain approach, to help give poor rural people the opportunities they so badly need. Furthermore, it is seeking more and better partnerships to support countries in improving the livelihoods of their rural population.

The Rural Poverty Report identifies an agenda for action around a broad approach to rural growth. It looks at how smallholder agriculture can be more profitable and better linked to modern markets, as well as more productive, environmentally sustainable and resilient to the growing challenge of climate change. It also identifies opportunities for growth and employment in the non-farm rural economy. The agenda needs to be appropriated and adapted to countries’ needs and local contexts. However, the report also makes it clear that implementing the agenda requires ‘joined-up’ government across different ministries, and a breaking down of some traditional distinctions between social and economic policies and programmes. It also requires a collective effort, including new partnerships and accountabilities, and new ways of working between governments, the private sector, civil society and rural people’s organizations, with the international development community playing a supporting or facilitating role as needed. If all of these stakeholders want it enough, rural poverty can be substantially reduced.

Mohamed Béavogui and Ides de Willebois

Introduction

|

||||

|

Tovoke (left) untangling a net with his neighbor Vontanà in Bema, Madagascar. | |||

For decades, agriculture in developing countries has operated in a context of low global prices for food products coupled, in many countries, with unfavourable domestic environments. Low levels of investment in agriculture, inappropriate policies, thin and uncompetitive markets, weak rural infrastructure, inadequate production and financial services, and a deteriorating natural resource base have all contributed to creating an environment in which it has frequently been risky and unprofitable for smallholders to participate in agricultural markets. Today, higher prices for agricultural products at the global level are contributing to creating a new environment within which smallholders must operate, and these may provide new incentives for them to engage profitably in markets. However, for this to happen, the domestic environment also needs to improve. In many countries, there remains anurgent need to develop appropriate policies, adopt or scale up successful approaches, and invest more and better in agriculture and in rural areas.

An enabling environment for agriculture needs to respond not only to longstanding issues and challenges, but also to newer realities. The natural resources on which agriculture is based – land and water above all – are becoming degraded and there is growing competition for their use. Climate change is already exacerbating this situation, making agriculture more risky, and it will have an even greater impact in the future. Domestic food markets are expanding rapidly and becoming more differentiated in many countries, offering new economic opportunities as well as risks for smallholders. International trade and market opportunities are also changing, with growing integration of global agricultural supply chains, and the emergence of large economies like Brazil, China and India as massive sources of both demand and supply of agricultural products. In many developing countries, rural and urban areas are ever more interconnected, and the changing nature of ‘rurality’ offers new opportunities for rural growth and poverty reduction.

In recent years, there has been renewed interest in agriculture as a key driver of development and poverty reduction. And in the aftermath of the food price surge, a number of global initiatives have emerged that seek to revitalize agriculture in developing countries. At the same time, growing attention is being given both to issues of adaptation to climate change in smallholder agriculture, and to ways in which poor rural people can participate in, and benefit from, market opportunities linked to environmental services and climate change mitigation. Also, the role of the state in agriculture and rural poverty reduction is being reassessed, and there is new interest in thinking through the role that public policies and investment can play in mitigating market volatility and assuring national food security.

There is broad agreement that growth in agriculture usually generates the greatest improvements for the poorest people – particularly in poor, agriculture-based economies. The Rural Poverty Report recognizes that agriculture, if better suited to meeting new environmental and market risks and opportunities facing smallholders, can remain a primary engine of rural growth and poverty reduction. And this is particularly true in the poorest countries. In all countries, however, creating new opportunities for rural poverty reduction and economic growth requires a broad approach to rural development, which includes the rural non-farm economy as well as agriculture. A healthy agricultural sector is often critical for stimulating diversified rural growth. But there are also new, non-agricultural drivers of rural growth emerging in many contexts, which can be harnessed.

|

||||

|

Bintou Sambou, 45, and her youngest child in the house she is building for her family in the town of Bignona, Senegal on Friday May 28, 2010. | |||

The basic premise put forth in this report is that the need of poor rural people to manage the multiple risks they face constrains their ability to take up new opportunities, in agriculture and the non-farm economy alike. Throughout the report, emphasis is placed on the crucial role that policies, investments and good governance can play in reducing risk and helping poor rural people to better manage them as a way of opening up opportunities. However, new forms of collaboration between state and society also need to be cultivated, involving rural people and their organizations, the business sector and a variety of civil society actors. These are crucial for the development of effective tools for risk management and mitigation.

The state of rural poverty today

The population of the developing world is still more rural than urban: some 3.1 billion people, or 55 per cent of the total population, live in rural areas. However between 2020 and 2025, the total rural population will peak and then start to decline, and the developing world’s urban population will overtake its rural population. In Latin America and the Caribbean, and in East and South East Asia, the number of rural people is already in decline. Elsewhere, the growth of rural populations is slowing. Numbers will start to decline around 2025 in the Middle East and North Africa and in South and Central Asia, and around 2045 in sub-Saharan Africa.

Despite massive progress in reducing poverty in some parts of the world over the past couple of decades – notably in East Asia – there are still about 1.4 billion people living on less than US$1.25 a day, and close to 1 billion people suffering from hunger. At least 70 per cent of the world’s very poor people are rural, and a large proportion of the poor and hungry are children and young people. Neither of these facts is likely to change in the immediate future, despite widespread urbanization and demographic changes in all regions. South Asia, with the greatest number of poor rural people, and sub-Saharan Africa, with the highest incidence of rural poverty, are the regions worst affected by poverty and hunger. Levels of poverty vary considerably however, not just across regions and countries, but also within countries.

Among the 1.4 billion people living in extreme poverty, there is a significant group, sometimes known as the ‘ultra-poor’, who are well below the poverty line. According to the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), there were half a billion people living on less than US$0.75 a day in 2004. Around 80 per cent of these people lived in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, and the very poorest overwhelmingly in sub-Saharan Africa; most of them are rural. In the poorest 5 per cent of households in the poorest areas of countries such as Kenya, Senegal and Mali, the incomes per person are a barely imaginable US$30 to US$50 per annum. Indeed, progress for these people since 1990 has been slower than for other groups among the poor, both in terms of income poverty and of hunger.

According to FAO, the numbers of undernourished people have been on the increase since the mid-1990s. Following the food price and economic crises, in 2009 the number of hungry people reached a billion for the first time in history. With improved economic growth and a decline in food prices, the figure declined in 2010 to 925 million.

Many countries have experienced significant growth over the past decade or two, but it has not always been accompanied by commensurate poverty reduction – especially where the growth has been driven by sectors other than agriculture. Growth in agriculture usually generates the greatest improvements for the poorest people – and particularly in the poorest, most agriculture-based economies. In recent years, there has been renewed interest in agriculture as a key driver of development and poverty reduction. And in the aftermath of the food price surge, a number of global initiatives have emerged that seek to revitalize agriculture in developing countries. At the same time, growing attention is being given both to issues of adaptation to climate change in smallholder agriculture, and to ways in which poor rural people can participate in, and benefit from, market opportunities linked to environmental services and climate change mitigation. Also, the role of the state in agriculture and rural poverty reduction is being reassessed, and there is new interest in thinking through the role that public policies and investment can play in mitigating market volatility and assuring national food security.

Rural poverty results from lack of assets, limited economic opportunities and poor education and capabilities, as well as disadvantages rooted in social and political inequalities. Yet large numbers of households move in and out of poverty repeatedly, sometimes within a matter of years. So while there are rural households that find themselves in chronic, or persistent, poverty, relatively large proportions of people are poor only at specific points in time. Data from countries as varied as Argentina, Bangladesh, Chile, China, Egypt, Ethiopia, Indonesia, the Islamic Republic of Iran and Uganda indicate that there are more people who are sometimes poor than always poor. The degree of movement in and out of poverty, and the speed with which people’s conditions change, are remarkable. Typically 10 to 20 per cent of the population fall or move out of poverty within a period of five to ten years. In the most extreme cases, more than 30 per cent of the population may fall into or move out of poverty.

Households fall into poverty primarily as a result of shocks such as ill health, poor harvests, social expenses, or conflict and disasters. Mobility out of poverty is associated with personal initiative and enterprise. It is highly correlated with household characteristics such as education and ownership of physical assets, and it is also dependent on good health. Beyond household-level factors, economic growth, and local availability of opportunities, markets, infrastructure and enabling institutions – including good governance – are all important. All these factors tend to be unequally distributed within each country.

Certain groups – particularly rural women, youth, indigenous peoples and ethnic minorities – are often disproportionately held back by disadvantages rooted in inequalities. Addressing these disadvantages requires building people’s assets and strengthening their capabilities – both individual and collective, while creating locally available opportunities and mitigating or helping them to better manage risks they face. Until recently, rural people’s capabilities have often been treated separately from investment in creating opportunities for rural development. However, these issues need to be tackled together in order to facilitate broad-based mobility out of poverty and to achieve inclusive, pro-poor rural growth.

The importance of addressing risks

Highlights from the report

|

||||

|

Pascaline Bampoky, 30, sits with her family outside their home in the town of Bignona, Senegal on Friday May 28, 2010. | |||

Avoiding and managing risk is a prerequisite for poor rural households to move out of poverty, and it is thus central to their livelihood strategies. At the household level, decisions about how to allocate and use cash, land and labour are a function not only of available opportunities, but also of the need to minimize the possibility of shocks that can throw the household into poverty, prevent it from moving out of it, or reduce its ability to spend on its primary needs. In many cases, however, the need to minimize these possibilities undermines people’s ability to seize opportunities, which generally come with a measure of risk. Rural households typically manage risk through diversification: smallholders may use highly diversified cropping or mixed farming systems. And many households use non-farm activities to complement and reduce the risks attached to farming – or vice versa. Asset accumulation – including money, land, livestock and other assets – is also critical to build a buffer against shocks, and a crucial component of risk management strategies at the household level.

Shocks are the major factor contributing to impoverishment or remaining in poverty. Poor rural people have less resilience than less-poor people because they have fewer assets to fall back on when shocks occur. When they do occur, poor people may have to resort to coping strategies that involve incurring debt, selling assets, or foregoing on education opportunities for children and youth – all of which leave them that much more vulnerable to future shocks.

The risk environment confronting poor rural people is becoming more difficult in many parts of the world. Not only do poor rural people face long-standing risks related to ill health, climate variability, markets, the costs of important social ceremonies and poor governance – including state fragility – but today they must also cope with many other factors. These include natural resource degradation and climate change, growing insecurity of access to land, increasing pressure on common property resources and related institutions, and greater volatility of food prices. In this environment, new opportunities for growth in rural areas are likely to be beyond the reach of many poor rural people. In many cases, innovative policies and investments are needed to address the new or growing risks, and to enhance responses to long-standing ones.

Putting a proper appreciation of risks and shocks at the centre of a new agenda for rural growth and poverty reduction requires a multi-pronged approach. On the one hand, it involves strengthening the capacity of rural people to manage risk by supporting and scaling up the strategies and tools they use for risk management and for coping, and helping them to gain skills, knowledge and assets to develop new strategies. On the other hand, it requires that the conditions they face be made less risky, be it in terms of markets, health care and other essential services, natural environment, or security from conflict. Specific areas of focus include strengthening community-level organizations and assisting them to identify new mechanisms of social solidarity; promoting the expansion and deepening of a range of financial services to poor rural people; and supporting social protection programmes that can help poor households to build their assets, reduce risks and more easily invest in profitable income-generating activities.

Agricultural markets for increased income

Highlights from the report

|

||||

|

Pascaline Bampoky, 30, pulls water from her neighbor's well in the town of Bignona, Senegal on Friday May 28, 2010. Since her family's well dried up, Pascaline has had to use the neighbor's well for all her family's water needs. | |||

Well functioning agricultural markets are essential for rural growth and poverty reduction. Most rural households are connected with markets, as sellers of produce, buyers of food, or both. However, the extent to which they are involved varies considerably. Market participation is often uncertain, risky and conducted on unfavourable terms. Under such conditions, many households seek to grow their own food rather than buying it in local markets, while others limit their investments in market-oriented crops in the absence of reliable produce markets.

Reducing risk and transaction costs along value chains is important for determining whether or not smallholders can engage profitably in modern agricultural markets. Strengthening their capacity to organize is a key requirement to participating in markets more efficiently and to reducing transaction costs for them and for those that they do business with. Infrastructure is also important – particularly transportation, and information and communication technology – for reducing costs and uncertainty, and improving market information flows. Contracts can help as they often build trust between smallholders and agribusiness. They also facilitate farmers’ access to input credit and other financial services. The growing importance of a corporate social responsibility agenda within the global food industry provides an increasingly positive context for the establishment of such contracts.

Agricultural produce markets have undergone profound transformations in the past two or three decades, in terms of the scale and nature of demand, and the organization of supply or market governance. In most developing countries, demand for agricultural products, particularly high-value ones, is increasing rapidly, with the demand driven by the growing numbers and increased incomes of consumers in urban areas. The rapid emergence of supermarkets is spurring the establishment of modern value chains, particularly for high-value foodstuffs. These are typically better organized, coordinated, and have higher standards than traditional markets, though the latter continue to play an important role in national food supply systems in most countries. Restructured or modern markets and value chains offer a new environment for smallholders, with potentially profitable opportunities set against higher entry costs and risks of marginalization. But traditional markets can offer an important alternative, and sometimes a fall-back option.

Global and regional agricultural markets are also becoming more integrated and concentrated in their structure. The map of global trade in agriculture has been changing, with some fast-rising economies playing a growing role. Many export markets tend to exclude small-scale suppliers, a process that has intensified with the imposition of higher product and process standards by northern retailers.

The degree to which smallholders are involved with agricultural markets varies greatly, depending particularly on household asset levels and location. In many countries, only between one- and two-fifths of the rural population are significant participants in agricultural markets, while some households, particularly in the most remote rural areas, may have little or no interaction with markets. A majority of poor rural households are, however, buyers of food – either net or absolute – and thus food markets are critical for them as consumers. And as non-farm income sources make up an ever-greater share of rural incomes, well-functioning agricultural and food markets will be even more important for food security in the future.

Access to remunerative and reliable produce markets can enable farming households to commercialize their production systems and focus on market oriented crops and livestock products, which can increase and secure their cash income and reduce the need for self sufficiency. In an example from Uganda, the Nyabyumba United Farmers Group received external substantial support to get to the point where it could become a supplier of potatoes to Nando’s fast food restaurants in Kampala. Having done so, its members, 60 per cent of whom are women, have gone from being reliant on off-farm labour and farming for their household food needs, to becoming specialized, fully commercialized producers who are able to use the income they earn to purchase their food needs. In Kenya too, a well-functioning dairy market has made it possible for smallholder producers on very small holdings to fully commercialize their production systems, zero-graze their animals using bought-in fodder and produce milk first and foremost for the Nairobi market. Producing market-oriented crops can also enable poor farming households to earn the income they need to purchase inputs for food crop production. Improved and less risky market access thus provides an important incentive for increased on-farm investment and higher productivity.

Faso Jigi and the cereal market in Mali

Faso Jigi was established in 1995 with the support of the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA) and the Quebecois agri-agency L’Union des producteurs agricoles – Développement international (UPA-DI), in the framework of a programme for restructuring cereal markets. Created as an association of farmer cooperatives, it aimed to facilitate smallholders’ access to markets and to obtain better and more stable prices for cereals (i.e. rice, sorghum and millet) and shallots. Over time, the collective marketing system set up in Faso Jigi gathered together important volumes of product, earning the organization significant bargaining power in local and national markets, and reducing transaction costs for both the farmers and other market actors thanks to economies of scale in storage and transportation.

The system also guaranteed stable farm prices and wide dissemination of market information on prices to smallholders, which also strengthened them with buyers. Faso Jigi also enabled members to have access to technical advice, which improved the quantity and quality of their yields, and to collective purchase of fertilizers, which ensured better prices and quality. Finally, the association has developed a mechanism of advanced payments to help its members address the problem of accessing working capital at the beginning of the agricultural season. Through the system, farmers receive loans against a delivery commitment to Faso Jigi. Faso Jigi then requests a loan from a financial institution based on the aggregated credit needs of its members, using its marketing fund as guarantee. An insurance fund has also been established to cover possible damages and price shocks. Since its establishment, Faso Jigi has become a remarkably successful organization, gathering more than 5,000 farmers grouped into more than 134 cooperatives. It sells more than 7,000 tons of cereals annually, valued at more than 2.5 million euros.

It has gained significant capacity to influence both markets and agriculture policies. Wholesalers prefer sourcing from Faso Jigi and are willing to pay higher prices because the association offers centralization of stocks, better quality in storage facilities and accessibility. However, cereal markets are in permanent change in the region, thus Faso Jigi must adapt its marketing system to stay competitive.

Source: “Faso Jigi: A people’s hope”

However, in Africa in particular, the lack of infrastructure is still an obstacle. Expansion of infrastructure related to energy, water and transport is occurring only slowly. The region continues to suffer from a large infrastructure gap (the density of paved roads in low-income countries in sub Saharan Africa is only one-quarter of low-income countries in other regions); and infrastructure services remain twice as expensive as in other regions. The overall impact on marketing costs can be major. Not only do transportation costs increase with the distance travelled, typically costs per kilometre are higher on dirt roads than on tarmac roads, and higher still where the dirt road turns into a footpath. For instance, surveys from Benin, Madagascar and Malawi find that transport costs can account for 50 to 60 per cent of total marketing costs.

|

||||

|

Bintou Sambou, 45, sits outside her home while filling small bottles with moukirr (a traditional healing ointment) in the town of Bignona, Senegal on Friday May 28, 2010. Bintou sells the ointment to supplement her revenue. Credit; ©IFAD/Olivier Asselin | |||

Addressing these problems, as well as improving the physical infrastructure, is an essential part of the enabling good governance environment that needs to be in place to reduce the costs and risks facing smallholders as they seek to access new market opportunities.

Today, however, information and communication technology (ICT), particularly mobile phones, is bringing a revolution in information even to remote rural areas. Use of mobile phones is expanding exponentially, and handsets are now affordable for many poor rural people. Mobile phones have greatly reduced market transaction costs for smallholder farmers, making it possible to find out product prices from markets (thus reducing risks related to unequal access to information), contact buyers, transfer money and arrange loans. More and more (short message service [SMS]-based) services of relevance to poor rural people are now provided by mobile phone. They provide information on agricultural markets, disease outbreaks and job markets, weather forecasts and technical advice – all important for strengthening rural people’s risk management and coping strategies.

Market information in Zambia: ZNFU 4455

The Zambia National Farmers Union’s market information system (ZNFU 4455) was designed in 2006 with the assistance of the IFAD-supported Smallholder Enterprise and Marketing Programme, to enable its smallholder membership to find the actual prices available in the market. To find the best price on offer, farmers send an SMS message containing the first four letters of the commodity and the district or province, to the number 4455. They immediately receive a text message listing the best prices and codes designating the buyers offering them. After selecting the buyer that best responds to their needs, farmers can send a second SMS with the buyer’s code. A text message is returned with the contact name and phone number. Farmers are then able to phone the buyer and start trading. Each message costs around US$0.15. The system works for 14 commodities and lists over 180 traders. Between its launch in August 2006 and August 2009, the system received over 165,000 hits. An estimated 15 per cent of initial SMS messages to the system led directly to farmers selling their produce, and over 90 per cent of the calls to buyers led to transactions.

Source: Milligan et al. (2009)

Also, governments have important roles to play in supporting the development of agricultural value chains in which smallholder farmers can find profitable, yet low-risk market opportunities. They need to develop enabling policies and regulations; invest in activities that promote the expansion and transformation of agricultural markets and specific value chains; support the capacity of poor rural people to engage in them more profitably; and encourage the private sector to invest in and source from smallholders and offer decent employment opportunities. They can also do much to reduce the risks and transaction costs for smallholders and other market actors.

There may on occasions be a case for governments to play a more proactive role in reducing market risk for smallholder farmers, as the example of COCOBOD in Ghana shows clearly.

Ghana’s cocoa marketing board

Resisting calls for liberalization in the 1980s, Ghana, the world’s second largest producer of cocoa, defended the value of its cocoa marketing board (COCOBOD). However, it liberalized small portions of the cocoa supply chain while streamlining COCOBOD’s operations so as to reduce its bloated costs and other implied taxes. Between the mid-1980s and early 2000s, COCOBOD reduced its workforce from 100,000 to 10,500; it spun off non-core activities to more appropriate government ministries; its rigorous quality-control procedures have ensured that Ghana’s cocoa continues to earn a premium on world markets; and it has significantly increased the share of the export price that goes to smallholder cocoa producers, using forward contracts to stabilize prices.

Source: IISD (2008)

Sustainable agricultural intensification

Highlights from the report

|

||||

|

A young boy stands in a field in Kossoye, Ethiopia. Lake Tana Watershed project area in the Amhara region. Kossoye is located in the Megech project area, Ethiopia. | |||

For food production in developing countries to double by 2050 it will require, above all, more intensive land use and higher yields. Over the past 40 years, growth in food production has more than kept pace with population growth, with enhanced agricultural productivity resulting in substantially increased global food supplies and, until recently, lower food prices. Yet there are concerns as to the environmental externalities of approaches to agricultural intensification based exclusively on the use of improved seeds and high levels of agrochemicals. Against a backdrop of a weakened natural resource base, energy scarcities and climate change, there is today a growing consensus that a more systemic approach is required.

While agricultural production in sub-Saharan Africa was growing almost as fast as the other regions at around 2.5 per cent per year, increased yields accounted for less than 40 per cent of the increase; the remainder – more than 60 per cent of the increase – could be attributed to expansion of land under cultivation and shorter fallow periods.

There were a number of technological successes, such as the rapid spread of improved maize in Eastern and Southern Africa, which now covers more than three-quarters of the land under cereal cultivation in Kenya, Malawi, Zambia and Zimbabwe; the adoption of high yielding varieties of NERICA rice, combining the best properties of Asian and African rice, on more than 200,000 hectares across Africa; and improved disease-resistant strains of cassava, which cover more than half of the cassava areas in Nigeria, now the world’s largest producer. Yet despite these real achievements, by 2002 improved varieties were planted on less than 25 per cent of the land under cereal across the region; fertilizer was applied at less than 10 kilograms of nutrients per hectare (a figure unchanged since 1980); and only 4 per cent of total cropland in this region was irrigated.

Agriculture has to become less risky for smallholder farmers, and it must be more sustainable as well as more productive. In the last decade or so, more and more scientists and social scientists have become interested in the idea of sustainability, and a whole range of terms, such as ‘agroecological approaches’, ‘ecologically intensive agriculture’, ‘low external input technology’ and ‘sustainable agricultural intensification’ have been coined to refer to this agenda of agricultural productivity with sustainability. Organizations of rural producers have also become supportive of a sustainable agriculture agenda, for a variety of reasons including concern with climate change or its role in a food sovereignty agenda; while farmers’ groups and NGOs too, particularly in Latin America and in Asia, have been experimenting with, and advocating greater institutional and policy space for, agricultural practices emphasizing sustainability.

In Androy, Madagascar, a local NGO (ALT) has been promoting the reintroduction of sorghum as a sustainable and drought-resistant crop and has also provided training for farmers in how to plant and look after the crop. IFAD has supported ALT to extend this reintroduction to more communities. “This is how they trained us… I didn’t follow the plough with the ampemba (sorghum), but tossed the seed over the ploughed area and covered it with my foot… Then after three days they sprouted… I didn’t plant it with corn… or where there was cassava. I didn’t plant it deep, or in places where there are ponds, and I didn’t drop many [seeds in each hole], but three or four… I found many young plants. I’d thin them out so that they won’t be dense. And if I found one with an insect in the head, I’d kill that and inspect the lower stalk also. So I’d cut that out, and it would re-sprout from the base, and I’d discard the wormy one at the edge (of the field). Then I’d look after the one I’d cut off, and it would produce other fine heads. So I had a good harvest, because I followed closely the discipline that those people gave us…” Randriamahefa, 49-year-old man, Madagascar.

However, land access and tenure security influence the extent to which farmers are prepared or able to invest in improvements in production and sustainable land management, adopt new technologies and promising innovations, or access finance for on-farm investment and working capital. Such issues need to be addressed as well.

Applying the principles – the System of Rice Intensification

The System of Rice Intensification (SRI) is a resource-conserving, but intensifying set of practices designed for well-watered environments. Developed in 1983 in Madagascar, its key principles are that rice seedlings should be transplanted when young, and widely spaced to permit more growth of roots and canopy. Rice field soils should be kept moist rather than saturated. Farmers are encouraged to experiment with these, to adapt them to local conditions and satisfy themselves that they are beneficial. Although some varieties respond better than others to SRI methods, it is claimed that increased yield is achieved with 80 to 90 per cent reductions in seed requirements and 25 to 50 per cent less irrigation water. Supporters of SRI report other benefits – resistance to pests and diseases, resistance to drought and storm damage, less pollution of soil and water resources, and reduced methane emissions. The benefits of SRI have now been documented in more than 40 countries in Asia, Africa and Latin America. In Cambodia, more than 80,000 families now use SRI practices, which are reported as leading to a doubling of rice yields, substantial reductions in the use of fertilizers and agrochemicals, and increases in farm profits of 300 per cent. Governments in the largest rice producing countries (China, India and Indonesia) are now supporting SRI extension and committed to significant expansion of SRI rice.

Sources: Prasad (2009); Uphoff (2009); Smale and Mahoney (2010)

Carbon sequestration through forestry: Trees for Global Benefits Programme, Uganda

The Trees for Global Benefits Programme in south-west Uganda has twin objectives related to PES and sustainable rural development. The programme supports low-income farmers to develop long-term sustainable land-use systems that incorporate carbon sequestration activities. Eligible carbon sequestration activities include agroforestry and small-scale timber; restoration of degraded or damaged ecosystems such as woodland; and conservation of forest and woodland under threat of deforestation. The ‘living plan’ (plan vivo) that is drawn up by each farmer shows the activities he or she will implement on the piece of land. The plans are assessed by the programme implementing agency for technical feasibility, social and environmental impact, and carbon sequestration potential. If approved, farmers or communities sign a contract or sale agreement for the carbon sequestered through their planned activities.

The development of a plan vivo is managed by Ecotrust, a local NGO, which provides farmers with financial and technical assistance and aggregates the carbon benefits of many communities or farmers through standard agreements. Private companies, institutions or individuals can purchase carbon offset certificates through the NGO, which also administers carbon payments directly to farmers. The carbon offset certificates are issued by an independently administered entity (Plan Vivo Foundation), following a standard process to evaluate the carbon benefits of each plan, based on internationally recognized technical specifications. Every certificate has a unique serial number to denote the exact producer, which provides buyers with distinct proof of ownership of the verified emission reductions and avoids double counting of carbon credits. The emissions certificates sold on behalf of the farmers or community represent the long-term sequestration of one ton CO2 equivalent.

The cost per ton of CO2 sequestered, ranges from US$6 to US$20, and includes the transaction costs for certification, verification and international support, local technical assistance, administration and monitoring, staged payments to farmers and a community carbon fund. An average of 60 per cent of the carbon offset purchase goes directly to the communities through instalments disbursed over many years. Payments to farmers are based on monitored results and later invested to improve and diversify farm incomes. Funding for the Plan Vivo Foundation comes from a levy imposed on the issuance of certificates and from implementing agency registration fees. The programme’s total carbon offset potential amounts to 100,000 tons of CO2 per year. For farmers, short-term benefits include income from payments (an expected US$900 over ten years) and a range of in-kind benefits from the trees. Long-term benefits are soil conservation and restoration of environmental and ecological functions in heavily degraded areas, including run-off and soil erosion control, microclimatic stabilization, terrestrial biodiversity, and shade for coffee plantations. All these result in higher yields and superior quality. Other benefits are expected to derive from the sale of high-quality timber harvested at the end of the rotational period. Improved understanding of agroforestry principles and land management techniques is also leading to increased productivity and food security.

Source: Di Stefano (2010)

The sustainable agriculture agenda has much to offer smallholders. Where market conditions provide an incentive for doing so, it can enhance productivity, make the most effective use of local resources, help build resilience to climate stress, and deliver environmental services – including some linked to climate change mitigation. Because sustainable agricultural intensification can be adapted to different requirements and levels of assets that men and women farmers have at their disposal, it can therefore be seen as a route through which they can broaden their options to better capture market opportunities while reducing risks, or strengthening their capacity to manage them.

Adequate incentives and risk mitigation measures need to be in place to enable smallholder farmers to make a shift to sustainable agricultural intensification. This requires, in particular, more secure land tenure and expanded markets for environmental services. Smallholder farmers must also develop the skills to combine their experience and knowledge with modern science-based approaches, and develop effective solutions to their problems. This will require strengthening agricultural education, research and advisory services, and fostering greater collaboration, innovation and problem-solving among smallholders, researchers and service providers. It will also require building coalitions, sharing responsibilities and creating synergies among governments, civil society, the private sector – and above all – farmers and their organizations.

Creating opportunities in the non-farm rural economy

Highlights from the report

|

||||

|

Ranotenie sorts sorghum in front of her house in Bema, Madagascar. | |||

Participation in the rural non-farm economy – both wage employment and non-farm self-employment – is an increasingly important element of the risk management strategies of large numbers of rural households. It is an important route out of poverty for growing numbers of rural people, particularly for today’s youth. Although this sector has been neglected by policymakers in many countries, today there is a new interest in promoting its development as a source of growth and of employment, in agricultural-based as well as transforming and urbanized countries.

Agriculture remains a key driver of non-farm economic development, with each dollar of additional value added in agriculture generating another 30 to 80 cents in second-round income gains elsewhere in the economy. However, nowadays there are four other important drivers that play a role in stimulating the growth of the non-farm economy. First, urbanization, and particularly the growth of small or medium-sized centres and the growing integration of rural and urban economies. Second, the processes of liberalization and globalization, which can create new employment and service opportunities in rural areas. Third, improved communication and information systems, particularly the diffusion of mobile phone coverage in rural areas. Finally, increasing investment in decentralized and renewable-based energy systems. These drivers may be present and combine differently within and across countries, creating different opportunities for the development of the rural non-farm economy.

If people are to harness these new drivers, there must be better incentives and fewer risks for everyone involved. This requires investment in rural infrastructure and services such as energy and transportation, and better governance. Prerequisites for encouraging private investments include improving the business climate, and providing business development and financial services suited to the needs of both men and women small entrepreneurs. For firms, the possibility of acquiring a labour force with appropriate skills is crucial. For rural workers, an improved environment is one in which they find decent employment opportunities and their rights and ability to organize are recognized, and in which efforts are made to address the prevalence of poorly paid, insecure and unregulated jobs – taken up predominantly by women – in the informal sector. Rural migrants want their rights to be recognized and their ability to organize supported, and they want to be able to send home remittances easily and at low cost. The role of government actors in creating an improved environment for the rural non-farm economy is important. However, an important part of that role may be to facilitate and catalyse initiatives taken by others such as firms or rural workers’ organizations.

Strengthening the capabilities of rural people to take advantage of opportunities in the rural non-farm economy is essential. Education and skills are particularly important, because they enable rural youth and adults to access good employment opportunities, and enhance their capacity to start and run their own businesses. Technical and vocational skills development in particular needs to be expanded, strengthened and better tailored to the current needs of rural people. These include microentrepreneurs, workers who wish to remain in their areas of origin and those who may seek to migrate.

Strengthening capabilities on all these fronts requires various, often innovative forms of collaboration, in which governments play effective roles as facilitators, catalysers and mediators; and the private sector, NGOs and donors are significantly engaged.

The importance of informal training for the rural economy – the case of Ghana

In Ghana, the informal economy employs almost 90 per cent of the labour force. Adequate education and skills training programmes targeting the informal economy are therefore critical for youth (rural and urban) to find good employment opportunities. However, while Technical and Vocational Skills development (TVSD) has been a concern of government in recent years, it has primarily targeted the formal rather than the informal sector, and despite the existence of a variety of public, NGO and private-sector programmes, informal on-the-job training represents the primary mechanism through which poor rural and urban youth develop their labour skills. Within the informal economy there are three types of such training, namely: traditional apprenticeship training in service and manufacturing, trade-related informal training in retail and farm-related informal training. All three have a number of advantages over formal training programmes.

They are directly relevant to the world of work; they enable youth to acquire practical, work-based competencies; they are low-cost and self-financing (through various trainee-master or within-family arrangements); and they nurture social capital and facilitate the establishment of informal business networks. Entry costs and opportunities are generally more favourable than in formal programmes to poor and rural people, including those without formal educational skills. On the other hand, these approaches tend to perpetuate traditional practices and technologies, encouraging replication rather than innovation and experimentation. Moreover, training is not necessarily delivered by people with good teaching skills, and the range of skills taught to trainees may be limited (including, in the case of girls, to traditional ‘women’s activities’), because of the context and specific purposes for which training is provided. Trainees also risk being exploited as cheap labour. For skills training in the informal economy to play a more effective role as a stepping stone for rural youth and adults to move out of poverty, greater support needs to go to informal training mechanisms, seeking to address their limitations without doing away with their specific advantages. Moreover, adequate support needs to go to the informal economy in which training takes place, so that good employment and entrepreneurial opportunities are available to those with enhanced skills. An adequate skills development strategy needs to recognize the multiple (formal and informal) paths through which rural youth acquire their skills as workers and entrepreneurs in the informal economy, and build on the specific strengths of each rather than pursuing mainstream formalization. In addition, it needs to recognize the importance of occupational pluralism in rural livelihoods, and seek to enhance both flexibility and breadth in existing formal and informal training.

Source: Palmer (2007)

‘Resource centres’ and rural microenterprise development in Burkina Faso It is not easy to establish enabling institutional and infrastructure conditions for microenterprise development. In Burkina Faso, a broadly favourable policy and economic context emerged in the 2000s. The IFAD-funded Rural Microenterprise Support Project (PAMER) took advantage of this, targeting rural women, youth, microentrepreneurs and poor farmers in need of alternative sources of income with business development services. In 2006, to ensure the sustainability of new enterprises and stimulate private-sector interest, PAMER established five resource centres in Garango, Ouargaye and Pouytenga in the Centre East region and in Orodara and Duna in the Western region. The centres provide a range of services, from support in setting up accounting systems and managing stocks, to help in identifying market opportunities. By 2008, PAMER had supported or helped people create around 2,700 microenterprises, with good results in terms of increased incomes. Women represented about two-thirds of microentrepreneurs accessing the services. Key success factors have been robust market demand for business development services in rural areas, which urban service providers could not meet; and the existence of rural service providers whose capacity could be nurtured relatively easily. Centre sustainability has been achieved by charging negotiated fees and enabling access to poor people while not subsidizing or crowding out owners of more developed enterprises, whose involvement has aided the financial viability of the centres. Given its success, support to 60 new centres is underway, funded by the government and IFAD.

Sources: IFAD (2007); UNDP (2009)

What needs to be done, and how?

Highlights from the report

|

||||

|

Bintou Sambou, 45, stands in the house she's building for her family in the town of Bignona, Senegal on Friday May 28, 2010. | |||

Ten years into the new millennium, the challenges of addressing rural poverty, while also feeding a growing world population in a context of increasing environmental scarcities and climate change, loom large. Robust action is required now to address the many factors that perpetuate the marginalization of rural economies. It needs to enable rural women, men and youth to harness new opportunities to participate in economic growth, and develop ways for them to better deal with risk. Above all, this action needs to turn rural areas from backwaters into places where the youth of today will want to live and will be able to fulfil their aspirations. How can all this be achieved? There is of course no simple answer. Countries vary profoundly in their level of economic development, their growth patterns, their breadth and depth of rural poverty, and the size and structure of their agricultural and rural sectors. Within countries, different areas can vary greatly, resulting in widely differing levels of opportunity for growth. As a result, there can be no generic blueprints for rural development and rural poverty reduction. The areas of focus, the issues to address and the roles of different actors will all vary in different contexts.

Nevertheless, there is a need to go beyond narrow or rigidly sequential sectoral approaches to rural growth. Agriculture continues to play a major role in the economic development of many countries, and to represent a major source of opportunities to move out of poverty for large numbers of rural women, men and young people – particularly those who can make it a ‘sound business’. In addition, in all developing regions smallholder farmers face major – if profoundly different – challenges. A focus on agriculture, aimed at assisting them to address these challenges, must remain a major thrust of efforts to reduce poverty and promote economic development alike. In all circumstances, the ultimate aim must be the development of smallholder farming systems that are productive, integrated into dynamic markets (for environmental services as well as food and agricultural products), and environmentally sustainable and resilient to risks and shocks. All three elements are essential features of a viable smallholder agriculture, particularly as a livelihood strategy for tomorrow’s generation. A vibrant agricultural sector as well as a variety of new factors can also drive the expansion of the non-farm rural economy, in a wide range of country circumstances. In order to broaden the opportunities for rural poverty reduction and economic growth, there is need for a broad approach to rural growth and emphasis on the larger rural non-farm economy.

A focus on these two areas – smallholder agriculture and the rural non-farm economy – requires particular attention to, and increasing investment in, four issues:

- Improving the overall environment of rural areas to make them places where people can find greater opportunities and face fewer risks, and where rural youth can build a future. Greater investment and attention are needed in infrastructure and utilities: particularly roads, electricity, water supply and renewable energy. Also important are rural services, including education, health care, financial services, communication and information and communication technology services. Good governance too is critical to the success of all efforts to promote rural growth and reduce poverty, including developing a more sustainable approach to agricultural intensification.

- Reducing the level of risk that poor rural people face and helping them to improve their risk management capacity needs to become a central, cross-cutting element within a pro-poor rural development agenda. It needs to drive support both to agriculture – and sustainable intensification reflects this concern – and to the rural non-farm economy. It involves developing or stimulating the market to provide new risk-reducing technologies and services for smallholders and poor rural people. It requires an expansion of social protection, and it needs to strengthen the individual and collective capabilities of rural women, men and youth.

- Advancing individual capabilities needs far more attention in the rural development agenda. Productivity, dynamism and innovation in the rural economy depends on there being a skilled, educated population. Rural women, men, youth and children all need to develop the skills and knowledge to take advantage of new economic opportunities in agriculture, in the rural non-farm economy, or in the job market beyond the rural areas. Investment is particularly needed in post-primary education, in technical and vocational skills development, and in reoriented higher education institutes for agriculture.

- Strengthening the collective capabilities of rural people can give them the confidence, security and power to overcome poverty. Membership-based organizations have a key role to play in helping rural people reduce risk, learn new techniques and skills, manage individual and collective assets, and market their produce. They also negotiate the interests of people in their interactions with the private sector or government, and can help to hold them accountable. Many organizations have problems of governance, management or representation, and yet they usually represent the interests of poor rural people better than any outside party can. They need strengthening to become more effective, and more space needs to be made for them to influence policy.

In the aftermath of the food crisis, the international donor community has taken a number of initiatives to support developing countries’ efforts to promote smallholder agriculture. It has also signalled a commitment to support developing countries’ efforts to mitigate and adapt to climate change. But investment in agriculture and the rural non-farm economy remains well below needed levels, and the momentum of these recent initiatives must be maintained. The proposed agenda in this report responds to the growing international concerns, while offering up ideas for concrete initiatives. Increasing investments in the areas highlighted in this report – some of which have been badly neglected in recent years – can support the piloting of new approaches and ways of working as a route for learning, promoting policy analysis and reform, and financing the scaling up of successful small-scale initiatives. In addition, many developing and recently developed countries have grappled with the issues addressed in this report. There is, therefore, enormous scope for increased levels of knowledge-sharing between developing countries.

There are today approximately one billion poor rural people in the world. Yet there are good reasons for hope that rural poverty can be reduced substantially, if new opportunities for rural growth are nurtured, and the risk environment improved.

What is at stake is not only improving the present for one billion poor rural people and the prospects for food security for all, but also the rural world and the opportunities within it that tomorrow’s rural generation will inherit.

Links:

- Rural poverty report

- Download the report English | French