What are the constraints and opportunities for Conservation Agriculture in Africa?

Over the past ten years there has been an endless debate over the relevance of the ‘Conservation Agriculture’ (CA) paradigm to the livelihood aspirations of smallholder farmers in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). In the realm of academic research, debate is welcomed and seen to strengthen and advance research. Unfortunately, when we move into the realm of development, the debates that take place between the promoters and skeptics on the ‘principles’ and ‘process’ of an intervention – in this case CA – may not help the development of sustainable production systems. In fact, it could be argued that such debates send the wrong messages to policy makers and donors.

From the growing body of literature, it is clear that neither the promoters nor the skeptics are 100 per cent right or wrong about CA. Irrespective of your position, it is crucial that we start to clearly document experiences with CA in a simple and open way, so that lessons and good practice can be shared and adapted to specific contexts. It is essential that the real constraints to the uptake of interventions be identified and reported. For example, what are the constraints to crop rotation, adoption of improved soil fertility and water management interventions, and improved germplasm? Many legume crops promoted for inclusion in a rotation require much more labour than a cereal crop, yet these issues are rarely considered.

These challenges will be further compounded in the near future by increasing daily temperatures, more erratic rainfall and a reduction in the length of the growing season throughout much of SSA, due to climate change. In fact, temperature increases will have greater negative impacts on crop production than the relatively small changes in rainfall, as the rate of plant development will be increased and crops will mature earlier. The adoption of existing recommendations for improved crop, soil and water management practices, even under climate change, will result in higher yields than smallholders are currently achieving under their low-input systems.

Regardless of whether you are for or against CA, it is imperative that participatory approaches are fully institutionalized in both research and extension agencies. Work being carried out by a number of centres of the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) as well as the Stockholm Environmental Institute, in collaboration with the African Conservation Tillage Network, has shown that the use of farmer-hosted demonstration trials encouraged the greatest participation, and subsequent adoption and adaptation of the technologies to suit specific needs.

Importantly, CA should not be considered as a panacea. It has the potential to work – it can shift some farmers in some agricultural systems onto sustainable production paths. But it requires pre-conditions and specific socio-economic and agro-ecological environments to work. It should be promoted on a demand-driven basis at the grass-roots level, based on solid technical packages and supported with long-term and consistent policies.

Stephen Twomlow PhD, CEnv

Climate and Environmental Specialist

Environment and Climate Change Division, IFAD

General feature on Conservation Agriculture

The world is facing one of its biggest challenges to date: producing more food for a growing population without increasing the land surface used to do so. It is estimated that by 2050, farmers around the world will have to produce 70 per cent more food to feed a growing, more urbanized population, and they will have to do so with the likelihood that arable land in developing countries will increase by no more than 12 per cent.

This monumental challenge can be met only if sustainability is the foundation of approaches to food security and poverty reduction in every country and every community. No other strategy has a hope of feeding current populations while protecting and restoring the natural resources that future generations will need to support their livelihoods.

“Land is each smallholder’s chief capital asset, and the quality of that land is one of the single most important factors in determining a smallholder’s quality of life. In order to improve nutrient content as well as productivity, traditional ‘business as usual’ production practices are no longer viable,” explained Geoffrey Livingston, regional economist at IFAD. “Responsible stewardship of land, water and tree cover is no longer just an option but rather an economic imperative for the vast majority of smallholders in the region.”

The agriculture sector will have to transform itself to become more community-focused, and establish an appropriate local balance of crops, livestock, fisheries and agroforestry systems to avoid overuse of pesticides and inorganic fertilizers and to protect soil fertility and ecosystem services – while increasing production and income. It will be imperative to work within ecosystems, using natural processes and a mixture of new and traditional technologies.

What is Conservation Agriculture?

Conservation Agriculture (CA) aims to achieve sustainable and profitable agriculture by promoting three principles: minimum soil disturbance, permanent soil cover and crop rotation.

It is only in the past ten years or so that government and development organizations in Africa have become interested in CA, after such methods proved their worth in Latin America. Early experiences on the continent have been relatively positive, but CA has yet to realize its full potential. To do so it needs to provide sustainable solutions to the many urgent problems African farmers are facing. These include soil degradation, loss of soil fertility, frequent droughts, labour shortages, and declining yields. According to the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa, environmental degradation is responsible for losses of between 4 and 12 per cent of gross domestic product.

Farmers are struggling to maintain crop yields as they confront droughts, rising sea levels and soil degradation. The growing demand for meat and dairy products among burgeoning middle classes in the more densely populated countries is raising pressure on scarce natural resources.

"In Eastern and Southern Africa alone, it is estimated that 10 of the 21 countries in the region are losing in excess of 60 kg of nutrients per hectare per year, gravely compromising the ability of farmers to maintain, let alone increase, productivity to raise household revenues and supply a growing demand for foodstuffs," said Livingston.

CA can provide an answer. In Africa many traditional farming systems have characteristics similar to CA practices. Tillage is often limited to planting in holes, mulching is practiced (using weeds, crop residues, grasses or green manure), as is direct planting with a hand hoe, and a wide variety of crops and trees are grown. In commercial agriculture, conservation or reduced tillage and direct planting, combined with the application of herbicides, have been widely practiced for some time. One of the first "No Till Clubs" was formed by a group of commercial farmers in KwaZulu-Natal in the 1970s.

"The principles of CA are not new to African agricultural systems, but the simultaneous application of its three principles has only recently been introduced," explained Esther Kasalu-Coffin, Country Programme Manager at IFAD.

Zero tillage, applied within a CA framework, has proven to be a feasible farming practice applicable under a wide range of climatic, soil and social conditions, both for large- and small-scale farmers. Crops are sown directly into a permanent soil cover, which can be either residues from a previous crop or a live cover crop. The permanent soil cover reduces the damaging impact of raindrops on the bare soil, retains soil moisture, regulates temperature, provides organic matter and is a potential source of nutrients. CA is attractive to farmers for several reasons: it saves time and money, it allows a longer period for planting, and it leads to greater drought tolerance and generally higher yields.

However, the impact and the practice of these techniques by smallholder farmers in Africa are still very limited. A number of constraints are impeding small-scale farmers from adopting such methods over the long term. They include a general lack of knowledge on how to introduce CA techniques and how to use the appropriate equipment and inputs (such as cover crop seeds and herbicides). There is also a lack of local infrastructure to support the manufacture and repair of CA equipment.

Land tenure is also a critical issue, as farmers will commit to managing the land only if land title and property rights are clearly defined. Tenure is also a constraint in situations where most of the land is collectively managed and where land is accessible to multiple users who often have contradictory interests in terms of land use – for example pastoralists and farmers. Farmers who have insecure tenure may be reluctant to adopt CA even though they see the benefits, because improving the soil productivity increases the risk of losing the land to more powerful people in the society. This is a major problem for landless persons and women heads of household. Equally, the availability of sufficient biomass, both in quantity and throughout the year, can also create problems. For instance, a lack of rainfall may hinder biomass production, and the available crop residues are needed for animal feed, fencing, fuel and other uses. The integration of livestock into CA systems is just as important, with controlled grazing, improved pastures, or better planning of animal feed demands in relation to crop rotations.

Support of government and development organizations

Despite the many constraints and challenges, the situation is gradually improving with the support of government and development organizations. Smallholder farmers, when guided by coherent policies and fair incentives, have shown they are willing and able to change how they do business (see the story on the use of cover crops in Uganda).

In the last decade, CA initiatives have started in countries (for example Kenya and Zimbabwe) where smallholders managed to increase yields considerably by applying conservation tillage techniques. The case study on Zambia shows how a government policy to introduce CA to small-scale farming has helped multiply yields threefold and started to improve farmers’ livelihoods, while protecting the local ecosystems. "Zambia tops the list of high uptake levels for sub-Saharan Africa as a result of targeting CA to smallholder farmers with a commercial interest in farming as well as promoting CA as part of a distinct farming system, not to mention the substantial investments in training of public and private extension services," explained Kasalu-Coffin.

Furthermore, sustainable innovations are bringing multiple benefits in terms of yield, profit, climate resilience and poverty reduction. For instance, in Malawi and Zimbabwe, planting acacia trees in maize fields has tripled yields and improved the resilience of the soil while boosting nitrogen content and water retention capacity and moderating the micro-climate. In an IFAD-supported project in Nyange village in Ngororero, Rwanda, students at a farmer field school are increasing yields by up to 300 per cent (compared to yields under traditional methods) by using integrated pest management and applying fertilizer only when there is a demonstrated need.

The African Conservation Tillage Network, founded in 1998 with the objective of promoting CA and exchange experiences among African farmers and other practitioners who work with them, is also contributing to the development of CA in Africa by bringing together farmers and policymakers who are dedicated to improving agricultural productivity while using natural resources sustainably.

With access to appropriate technologies and innovations and relevant training, farmers have produced results with multiple benefits for communities, ecosystems and natural assets as well as themselves. In the short run, however, without such support and an adequate policy environment, smallholders operating near or under the poverty line may not always prioritize sustainable approaches. Where the right policies and incentives are in place, smallholders have shown they will take a long-term view, prioritizing sustainable techniques.

Access to green technologies

For conservation agriculture to be successfully introduced, farmers must also be given incentives to use energy-saving technologies – solar systems, wind energy and biogas – which they often overlook because of their relatively high purchase cost. To this end, they need to have access to microfinance to invest in such technologies and turn away from traditional energy sources (wood, diesel and kerosene), which are just as expensive in the long run and damage the environment.

The same principle applies to managing water resources, which are often wasted and become scarce because of lack of adequate or appropriate management. A project in Madagascar introduced drip irrigation, a new technology which enables farmers to irrigate their crops while minimizing the amount of water being used. As a result, many farmers increased their yields (see story below).

Equally, financial incentives must be given to farmers for sustainably managing natural resources. In Kenya, the Green Water Credit initiative provides regular payments to downstream water users in recognition of their important role in managing land and water resources. This enables farmers to invest time and resources in green water management, while diversifying their income and helping them to stay out of poverty (see: www.greenwatercredits.org).

Another impressive example is Songhai, the agricultural entrepreneurship training centre established in Benin, and since replicated in numerous countries in SSA. This initiative focuses on providing an entrepreneurial platform for young African farmers to develop skills to practise sustainable, profitable agriculture. Activities at the centres focus on green technologies and renewable energy as well as business and life skills training. Songhai values the principle of working in harmony with local ecosystems, and centres are adapted to the realities of the environments in which the trainee farmers operate. In 2008 the United Nations promoted Songhai as a Centre of Excellence for Africa by the United Nations.

Further investment in agricultural science research is needed if sustainable intensification is to contribute to raising agricultural productivity. Support for research in developing countries is generally inadequate and is being scaled back. Reversing this trend is urgent, and more resources must be spent on the challenges that smallholder farmers face.

For further information:

- Stephen Twomlow

Climate and Environment specialist

Environment and Climate Change Division, IFAD

- Geoffrey Livingston

Regional Economist

East and Southern Africa Division, IFAD

- Esther Kasalu-Coffin

Country Programme Manager

Latin America and Caribbean Division, IFAD

- IFAD's governing council on conservation agriculture:

- IFAD Social Reporting Blog

Stories from the field

Zambia: a case study on Conservation Agriculture

Persistent food insecurity

Zambia is a food-insecure country despite excellent soils, relatively good rainfall (with the exception of normal climatic variation) and a population density of only 14 per/km2 (compared, for example, with 150 per/km2 in Malawi). Factors that contribute to the country’s food insecurity are: land degradation, mainly due to consistent monocropping of maize and fuelled, since the mid 1970s, by a succession of government policies of input supply and marketing subsidies to small-scale farmers; and conventional methods of production, involving ploughing and the repeated use of acidifying fertilizers, which lead to depletion of nutrients and loss of soil structure.

As an example, before the mid 1970s, the Southern Province in particular was a net exporter of between 200,000 to 300,000 tons of maize. Today it is a net importer, and the provision of food relief is commonplace. Over the past 20 years, thousands of families have migrated northwards to other provinces in search of more reliable food supplies. As a result, thousands of hectares of increasingly degraded land were abandoned, as the land had lost its nutrients because of intensive and monocrop farming.

History of Conservation Agriculture in Zambia

Modern CA in Zambia emerged as a by-product of technology transfer by large-scale commercial farmers. Commercial farmers adopted foreign minimum tillage systems for their own use, and later supported scaled-down versions for smallholder farmers living in low- to medium-rainfall regions.

The technology was formally introduced to smallholder farmers in Zambia in 1996 by the Conservation Farming Unit (CFU) following the 1995 drought.

The government’s strategy for promoting Conservation Farming (CF) aims to reverse deforestation and adopt CA to achieve the following:

- bring soils back to life and increase yields and incomes

- enable sedentary farming (farming in the same place) in perpetuity;

- enhance household food security and diet through crop diversification and rotation;

- increase resilience of crops to droughts and poor rainfall distribution.

Government policy, strategy and programmes

Promotion of CA is included in the Zambian National Agricultural Policy 2004-2015. The Ministry of Agriculture and Co-operatives has a climate change adaptation and mitigation agenda. CA is one of the areas that has been identified as a potential area for adaptation. The areas include:

- building adaptive capacity to enable farmers to better cope with increasing vulnerability from climate change;

- government-led sustainable land management in Miombo, ecosystem management in Mkushi and Serenje Districts, with efforts to scale up support in the Copperbelt, Northern, Luapula and North-Western provinces;

- Conservation Agriculture for Sustainable Agricultural Development Programme, which aims to harness early land management potentials for in-situ rainwater harvesting for crop, fish and livestock production; and

- adaptation to climate variability and change in order to improve food security, which will involve revising the National Fiscal, Regulatory and Development Policy to promote adaptation responses in the agriculture sector.

The largest programme currently being implemented by the CFU, and financed by the Government of Norway, is the Conservation Agriculture Programme (from 2006 to 2011), which aims to have 240,000 small-scale farmers using CA techniques by the end of 2012. According to CFU estimates, more than 65 per cent of the target has already been reached.

Promoting Conservation Agriculture technology

CA technologies being used in Zambia are the most advanced and widespread in Southern Africa. The reasons for this are many, but chief among them are:

- CA aimed at smallholder farmers with commercial interests in farming, as opposed to very resource-poor farmers producing largely for subsistence. The CFU of Zambia deliberately targeted cotton farmers who had access to inputs and extension advisory services from the cotton companies. They expected farmers to be interested in higher yields and higher incomes from cotton, and also anticipated that it would be easier to demonstrate the positive results of CA to other resource-poor farmers, using evidence from smallholder cotton growers' fields.

- Demonstration of CA as part of a distinct farming system and not just as a technology. Maize and a legume crop (cowpea in Central, Eastern and Western parts of Zambia) were promoted as a component of the cotton CA system. Maize was included in the crop system because farmers already grew it as a main food crop. In addition, maize production was used as a source of soil nutrients. Farmers would add fertilizer to the crop and not to cotton or cowpeas. Using the rotation system, it was recommended that cotton be planted after a fertilized crop of maize, thus benefiting from the residual fertilizer. The cowpea crop also served two purposes: as a source of organic fertilizer (nitrogen fixation from the legume) and a good source of protein in the diet. When a maize crop followed cowpea in the rotation, the amount of fertilizer added to it was also reduced because of the nitrogen contribution from the cowpea crop. The cowpea crop also benefited from the system, being highly susceptible to insects. To obtain reasonable yields, cowpea requires insect pest control. To attain good yields in a cotton-cowpea system, the cotton is sprayed as it suffers more from insect pest damage than cowpea. In this system the insecticide sprayed on the cotton drifts to the cowpea and effectively controls cowpea pests at no extra cost.

- Large CFU investments in the training of public and private extension services. They in turn trained lead farmers to provide technical support to other farmers for scaling up CA in Zambia. Most of the training at the farmer group level is conducted by farmer facilitators. There is minimal ‘free input’ distribution to farmers under the CFU programmes. The fertilizer and seed are provided by the cotton companies in a loan package.

- Tools and equipment to reduce labour. These include small planting and weeding tools to help open the planting holes under minimal soil disturbance operations.

- A supportive government policy environment, which promotes and to some extent subsidizes CA methods.

What is manual minimum tillage?

Manual minimum tillage is the most common form of CA technology promoted in Zambia. It is characterized by planting stations (basins) that rely heavily on hand hoes and to some extent on animal draught power. The level of mechanized minimum tillage is very low, and very few farmers apply no-tillage.

Ideally, the technology involves the application of seven practices:

- preparing land during the dry season;

- establishing a precise and permanent grid of planting stations, furrows or contoured ridges within which successive crops are planted each year and within which fertilizers can be accurately applied;

- restricting land tillage and nutrient application to 15 per cent of surface area where crops are sown;

- rotating a cereal and a cash crop with nitrogen-fixing legumes;

- retaining at least 35 per cent of crop residues in fields and discontinuing residue burning;

- applying cattle manure or fertilizers in basins; and

- retaining mulch or residues from the previous season’s crop.

The progression to CA involves introducing perennial crops and trees into a CA system that is based on the production of annual crops

Benefits of CA methods for smallholder farmers

There are many benefits for smallholder who adopt CA:

- The government gradually reduces, and eventually withdraws, the provision of fertilizer subsidies for maize production.

- Farmers are no longer dependent on chemical fertilizers, which would increase input use efficiency and reduce production costs, allowing farmers to effectively compete in the regional maize market.

- Household food security and dietary intake would improve, ending food relief, except for the most disadvantaged and vulnerable households.

- Resilience to climate change shocks would be strengthened.

- A more robust and diversified production base and the regeneration of soil fertility would put farmers in a much stronger position to grasp future economic opportunities.

- Small-scale agriculture would be able to sequester carbon or contribute to emissions reduction rather than contributing to its increase

In Zambia, significant differences in yield levels between conservation and conventional tillage systems have been recorded in farmers’ fields. While the average yield of maize under conventional farming is between 1 to 1.5 tons per hectare, commercial farmers adopting CA techniques have recorded more than 5 tons per hectare. Almost all small-scale farmers have much higher crop-yield levels per hectare under CA.

Main constraints to farmers’ adoption of conservation agriculture

Crop residues. Traditionally, crop residues are not retained as mulch but burned as a quick way to clear agricultural fields, thus facilitating further land preparation and planting. This is a conventional method of production in parts of the country where farmers own few livestock and rely on hand hoes for tillage. However, in areas such as the Southern Province there is competition for crop residues from livestock.

Herbicides. In Zambia, many small-scale farmers do not use herbicides as they cannot afford them. This places a huge demand on an already stretched rural labour force. Without the use of herbicides, adoption of CA increases labour requirements, especially for weeding and preparing basins during the early years of adoption. Labour constraints also limit the amount of land that can be cultivated. Often farmers face difficulties in cultivating more than two hectares of land without the use of herbicides.

External inputs. Farmers have difficulties accessing and using external inputs. Most importantly, the government fertilizer and seed subsidy scheme for smallholders is often tardy, and only a few growers benefit (an estimated 20 per cent). There are on-going efforts to adapt various types of CA equipment for smallholder farmers. The CFU and the Golden Valley Agricultural Research Trust are working with private-sector partners to develop local CA equipment. However, one challenge they face is the high import duty that the government levies on steel, which makes it economically unviable for CA equipment to be manufactured locally.

Crop rotation. Most farmers who adopt CA do not practise adequate crop rotation, and instead many of them choose to cultivate more maize. Some farmers consider the recommendations for permanent planting basins to be unsuitable for growing other crops such as legumes. Furthermore, the limited markets for such crops reduce incentives for their cultivation.

Scaling up conservation agriculture activities

With a more concerted effort, the country could reach landscape-level adoption of CA, with significant benefits that would help address household and national food security. The Conservation Agriculture Programme has been very successful and is being used as a model for scaling up CA in Zambia and elsewhere in Africa.

Extract from IFAD's publication: Smallholder conservation agriculture. Rationale for IFAD involvement and relevance to the East and Southern Africa region (September 2011).

For further information:

Esther Kasalu-Coffin

Country Programme Manager

Latin America and Caribbean Division, IFAD

Fumiko Nakai

Country Programme Manager

East and Southern Africa Division, IFAD

Uganda: the use of cover crop among oil palm growers

|

||||

|

Field officer Charles Kateregga of KOPGT demonstraes how to make cover crop seedlings for planting. ©IFAD | |||

Cover crops are one of the most common techniques used in Conservation Agriculture (CA). They are planted primarily to increase soil fertility. The technique was taught to small-scale farmers in Uganda as part of the IFAD-supported Vegetable Oil Development project, which introduced oil palm plantations in 2004 on Bugala island on Lake Victoria. The objective of the project was to reduce Uganda’s heavy reliance on vegetable oil imports – palm oil in particular – by supporting palm oil production, agro-processing and marketing. Small-scale farmers were encouraged to grow oil palm; by integrating small-scale production with large-scale processing, small producers are becoming part of the mainstream economy.

Keeping the soil alive by using cover crop in oil palm farms on Bugala

Cover crop plays an important role in fixing the nitrogen content, which improves the nutrients in the soil and traps the water to avoid run-off and soil erosion. It also prevents moisture from escaping. The dead leaves of the cover crop fall off and serve as mulch for the soil. At the same time, the use of cover crop reduces the costs of farm maintenance because the farmers do not have to clear huge sections of weeds from their gardens. In the long run, a reduction in costs implies that the farmers’ income increases.

|

||||

|

A portion of the newly planted nucleus estate covered with the mucuna covercrop. ©IFAD | |||

As part of the project, environmental studies were carried out and recommendations made to ensure sustainability of resources. The National Environment Management Authority also provided guidelines to be followed by oil palm growers such as leaving a 200 m border between the plantations and the lake and other water sources. Farmers were also introduced to the use of cover crop in their gardens. On Bugala, there are several types of cover crop – mucuna blactiata, puereria japonica and centrocema.

According to Charles Kateregga, a field officer for the Kalangala Oil Palm Growers Trust, the trust representing smallholders, the farmers had to be taught about the benefits of planting cover crop, as well as the cost and maintenance. "The first ones to adopt cover crop in their gardens right now are the envy of their fellow oil palm growers because their plants look good, and they do not have to spend a lot of money and time on clearing weeds," he explained.

|

||||

|

Musiimenta (in green overalls) and his wife (back to the camera), being interviewed by a researcher in their plantation. ©IFAD | |||

One such farmer is Edson Musiimenta and his wife Rose Mary Nabukeera. Their entire 20-acre (8 hectares) plantation is covered with the mucuna cover crop, and their highly productive plantation has become a model for other farmers. Musiimenta said he planted cover crop because the field officers taught him that it helps keep the soil moist, prevents erosion and adds nutrients to the soil. “I did not want anything to jeopardize my oil palm trees because I knew I had to make enough money to pay back the loan once the harvesting started. I followed all the instructions and advice of the Mulimisa [field officer]. When they said cover crop was good and there were seedlings, I planted,” he explained. In addition, Musiimenta has taken the advice of the field officer to grow cover crop seedlings to sell to other farmers. “Now, most of them want them and have to plant them. My wife and I are in the process of establishing a nursery bed for this,” he added.

Unfortunately, only about 10 per cent of the farmers have planted cover crop. At first, the option was left to the farmers and most of them chose to intercrop the palms with food tubers such as sweet potatoes. Intercropping works when the palms are still young, but as they grow, both crops start competing for nutrients. Now, intercropping is being discouraged by field officers, who put pressure on farmers to plant cover crop with oil palms, and to keep a portion of their plot for food crops. Slowly, they are beginning to understand the benefits of carefully planning the use of cover crop to protect their palm plantation, while at the same time growing enough subsistence crops for their own needs, but in separate plots. When farmers see their neighbours’ success, they quickly adopt the method.

For further information:

- Ann Turinayo

Knowledge Management and Communications Officer

East and Southern Africa Division, IFAD in Uganda - Carole Idriss-Kanago

Associate Country Programme Manager

East and Southern Africa Division, IFAD in Uganda - Alessandro Marini

Country Programme Manager

East and Southern Africa Division, IFAD

Useful link:

Madagascar: introducing the drip irrigation technology

|

||||

|

The 100 m2 kit disseminated by SCAMPIS in Madagascar : in blue, the sturdy plastic bag used as a water tank ( capacity 50 gallons) , mounted on a stand about 1 m above ground . In the forefront : the black polyethylene tapes used to convey the water; in the bottom left, one can discern (inserted in the tape) the microtubes used as drippers. ©IFAD | |||

Drip irrigation is an irrigation method that saves water and fertilizer by allowing water to drip slowly to the roots of plants, either onto the soil surface or directly onto the root zone, through a network of valves, pipes and emitters. It is done with the help of narrow tubes that deliver water directly to the base of the plant. Drip irrigation technology is one alternative that improves the distribution of water (with the help of irrigation ramps) and also reduces the amount of water that is brought to each plant. The efficiency and cost-effectiveness of drip irrigation are notably superior to more traditional irrigation methods.

The technology was first introduced in Madagascar by the Scaling Up Micro-Irrigation Systems project (SCAMPIS), which adapted the kit to the local environment and subsidized some of the equipment. SCAMPIS aims to promote water security for poor rural households. It was soon taken up by the Programme d’appui à la résilience aux crises alimentaires à Madagascar (PARECAM or Programme to Support Resilience to Food Crises in Madagascar), a programme funded by the EU Food Facility which was implemented through the IFAD-supported projects already in place on the island. Together PARECAM and SCAMPIS subsidized 85 per cent of the kits and 100 per cent of the pumps. A system costs approximately US$ 70 and a pump (which can be used for more than kit) costs around US$95, which remains rather costly for the poorest producers.

In order to keep the cost as low as possible, different drip kits were devised for land areas of 50m2, 100m2 and 200m2. Water pressure is regulated from an elevated reservoir that is fed by a pedal pump. One reservoir can feed several drip kits. In theory, a farmer can gradually extend the irrigated surface by purchasing additional kits, which can be used individually or collectively. The more kits that can be fed by one water source, the more cost-effective the system is.

|

||||

|

Close-up of the drippers. ©IFAD | |||

|

||||

|

Showcase at a dealer’s shop : the kit parts are exposed as well as ( in blue ) the treadle pump. ©IFAD | |||

In 2009-2010, SCAMPIS set up 97 demonstration sites around 550 parcels of land in more than 60 rural communes. The results clearly indicated a greater efficiency and value than had been anticipated. The sites also paved the way for disseminating the technology and kicking off local production of the required material. From this highly positive experience, the project linked with IFAD projects and PARECAM to upscale and replicate its successes, especially in the southern region of the country where there are regular water shortages.

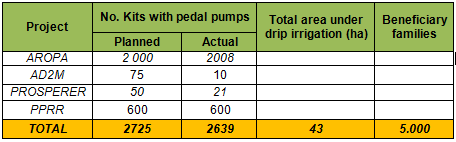

In 2011, a total of 2639 kits were provided with 1158 pedal pumps: 2008 for the Support to Farmers’ Professional Organizations and Agricultural Services Project (AROPA); 600 for the Rural Income Promotion Programme (PPRR); 21 for the Support Programme for the Rural Microenterprise Poles and Regional Economies (PROSPERER); and 10 for the Project to Support Development in the Menabe and Melaky Regions (AD2M). They represented about 43 hectares benefiting nearly 5,000 vegetable growers.

Drip kits implemented with pedal pumps

Furthermore, in order to promote a commercial network for the technology, and thus reduce the costs, SCAMPIS is introducing a market-oriented phase in 2012. Currently commercial venues to purchase the kits are under-developed, or non-existent, in most of the programme’s regions. Overall, the PARECAM/SCAMPIS experience demonstrated the potential of drip irrigation technology as a poor-friendly technology, when used in its basic and simplified version. Paring the cost of the technology down to the minimum and using normal market processes to mainstream it hold great promise.

|

||||

|

Demonstration of the kit operation at a market. ©IFAD | |||

The experience in Madagascar shows that:

- Drip irrigation technology, in its simple form, is particularly suited to very small-scale, resource-poor farmers, requires little capital for small plots, is easy to manage, saves labour and, most importantly, can significantly enhance productivity of land and water, quality of the produce and the farm income of the households that adopt the technology.

- Drip irrigation technology has responded to two critical but distinct needs: of poor (women) to create a new means of income and livelihood; and of farmers in water-scarce areas to cope with the scarcity. The best examples are to be found in the South, where micro-irrigation groups (mostly poor women vegetable growers) created by PARECAM have improved their cash income and household food and nutrition security.

- A small-scale, water-efficient irrigation technology like drip irrigation is an effective tool for food security among smallholder farmers. Targeted, homestead-scale support through the technology, using scattered small water sources, is the appropriate way to achieve a more integrated set of poverty impacts than conventional water services.

- Smallholder irrigation farmers are potential investors as they seek opportunities to attain food security, create wealth and generate employment opportunities rather than rely on handouts and relief food.

- The successful promotion of drip irrigation technology should create the highest impact in the shortest time possible – a process that is cost-effective, self-sustainable and income-generating, and that can be scaled up or replicated.

|

||||

|

Operation of the locally-made treadle pump promoted by SCAMPIS and PARECAM; The white bag is the tank for a 50 m2 kit. ©IFAD | |||

For more information:

Norman Messer

Country Programme Manager

East and Southern Africa Division, IFAD

Caroline Bidault

Associate Country Programme Manager

East and Southern Africa Division, IFAD

Audrey Nepveu de Villemarceau

Senior Technical Adviser

Policy and Technical Advisory Division, IFAD

Carla Ferreira

Former Country Programme Manager for Zambia and Rwanda, Carla Ferreira, has been temporarily transferred to IFAD’s Corporate Services Division as an Administrative Officer. This provides Carla with an opportunity to apply her eight years of experience as a CPM to support IFAD’s Human Resources Reform agenda. As many of you know, Carla has recently had her first child, so the move also enables her to spend more time in Rome.

As an elected member of the IFAD Staff Association’s Executive Committee (ECSA), Carla was already familiar with the HR reform process.

Carla is looking forward to returning to ESA in 2013, and to applying her newfound experience to her work as a CPM. When asked what she misses about working as a CPM in ESA, she replied “ my colleagues, the country project staff, and visiting the projects”.

We look forward to welcoming you back next year Carla!

Helen Gillman

Helen Gillman, Knowledge Management Officer and Coordinator of the ESA newsletter transferred to IFAD’s Strategy and Knowledge Management Department as of July 2012. Helen has worked in ESA for nearly four years. In that time she has worked closely with Country Programme Managers, Country Officers and staff of IFAD-supported projects to integrate knowledge management into project design and implementation, as a means to improve performance, results and impact. This has resulted in the development of a model for an integrated knowledge management and learning system for improved project performance. Helen has also worked extensively on the grants portfolio, task managing numerous grant programmes, as well as supporting major capacity building initiatives in ESA.

Loans and grants approved at the April 2012 Executive Board

Kenya

- Upper Tana Catchments Natural Resources Management Project US$ 32 million

Regional Grants

-

Alleviating poverty and protecting biodiversity through Bio Trade - Phyto Trade Africa – US$ 1.5 million

Loans and grants to be submitted to the September Executive Board

South Africa

- South African Market-Led Smallholder Agricultural Development Programme US$ 16 million

Mozambique

- Pro-Poor Value Chain Development in the Maputo and Limpopo Corridors, US$ 18 million

Workshops

IFADAfrica workshop

A regional Knowledge Management and Learning Workshop was held from 19-22 June in Nairobi, Kenya, for staff of IFAD-supported projects and country offices in East and Southern Africa (ESA). The workshop was hosted by IFADAfrica, ESA’s regional knowledge network. It represented the culmination of the regional KM and learning initiative implemented by IFADAfrica over the past three years, in which 125 project staff from 32 projects in 12 countries, CPMs and Country Officers, as well as a more limited number of staff from government departments and partner organizations, have participated. They have learned how to operationalize effective knowledge management and learning in their projects and anchor it in the country programmes. Many projects also received coaching on KM&L. Ultimately, successful KM will contribute to enhanced project effectiveness.

The main outputs of this KM sharing event were:

- Enhanced sharing of the different ways projects have implemented KM&L, their challenges and successes - and a deeper understanding of the practice around it.

- A set of KM&L methodologies and tools which have worked well.

- A more structured and linked system for sharing and joint learning, using various methods and mechanisms to continue learning. This will involve the formation of a range of communities of practice across projects.

- Documentation of good practices and impact achieved in the field. Stories will be captured and impact analysed.

- A work plan for adapting and operationalizing the broader KM and learning system in the countries and projects.

IFADAfrica’s second phase will start in July this year. During the new phase, IFADAFRICA will continue working to strengthen KM at project/programme and country programme levels. IFADAfrica will focus on putting the integrated KM system developed during Phase 1 into practice, testing and applying the framework with project and government staff: learning what is needed to make the KM&L system work, in terms of capacity, support, resources and changes in management processes etc. Phase 2 will also focus on developing the competencies that project and government staff need to incorporate the integrated KM system into their daily work. As well, IFADAfrica will strengthen peer learning and exchange across projects, both on methodological and thematic issues. It will also support the emergence of service providers in the region who can provide KM and networking support to projects and IFAD partners into the future.

.

Missions

Botswana

- The Start-up Workshop for the Agricultural Services Support Project (ASSP) took place in Gaborone from 23 to 26 April 2012

Burundi

- The President of IFAD paid an official visit to Burundi from 28 to 31 March 2012.

Kenya

- The Annual COSOP review was held in Embu from 7 to 9 March 2012. The participants included the full Kenya Country Progrqamme Management Team, grant projects, the IFAD Director of ECD and representatives from FAO and WFP.

- The ESA Director visited Kenya on 27 March 2012 and attended meetings with the permanent secretaries of the Ministries of Finance, Agriculture, Livestock, and Water Resources & Irrigation.

- A Supervision Mission for the South Nyanza Community Development Project (SNCDP) took place from 2 to 11 May 2012.

- A Supervision Mission for the Mount Kenya East Pilot Project (MKEPP) took place from 21 May to 4 June 2012.

- A Supervision Mission for the Programme for Rural Outreach of Financial innovations and Technologies (PROFIT) took place from 25 to 29 June.

Uganda

- An Implementation Support mission took place for the District Livelihoods Support Programme (DLSP) from 20 to 23 March 2012.

- An Implementation Support mission took place for the Community Agricultural Infrastructure Support Programme (CAIIP) from 27 to 30 March 2012.

- The Country Programme Management Team (CPMT) meeting was held on 29 March 2012. During the meeting, the projects shared lessons learned from project implementation, outcomes and impacts that will inform the COSOP which is under formulation.

- The Start-Up Mission of the second phase of the Vegetable Oil Development Project (VODP2) took place from 30 April to 11 May 2012.

- The President of IFAD paid an official visit to Uganda from 5 to 8 May 2012.

- A Supervision Mission of the Rural Financial Services Programme (RFSP) took place from 7 to 18 May 2012.

- An Implementation Support Mission for the Vegetable Oil Development Project (VODP2)-Oil Palm component took place from 16 to 30 June 2012.

- A Country Programme Evaluation (CPE) was conducted based on the COSOP of 2004–2009. The results of the CPE will also inform the current COSOP formulation process. The CPE National Roundtable workshop was held on 12 July 2012. The workshop brought stakeholders together and provided a platform for reflection on the main findings and recommendations from the CPE.

- A Supervision Mission of Full supervision of District Livelihoods Support Programme (DLSP) is scheduled to take place from 16 to 27 July 2012..

Zambia

- A Financial Management Oversight and Support Mission for the Smallholder Livestock Investment Project took place from 5 to 16 March 2012.

- The Country Programme Management Team held its Annual Review Workshop from 19 to 23 March 2012.

- A Supervision and Implementation Support Mission for the Smallholder Livestock Investment Project took place from 16 to 27 April 2012.

- A Supervision and Implementation Support Mission for the Smallholder Agribusiness Promotion Programme took place from 4 to 15 June 2012.

Appointments and staff movements

Périn Saint Ange

Mr Saint Ange, a national of Seychelles, was appointed as the new director for ESA and took up his appointment on 13 February 2012. Mr. Saint Ange has worked with IFAD in varying capacities since March 1998; his last position was as Portfolio Adviser in the West and Central Africa Division. He has wide experience in development, including as an Agricultural Economist in the Investment Centre at FAO and as the Seychelles Principal Secretary/Director General at the Ministry of Agriculture.

Lorenzo Coppola

Mr Lorenzo Coppola joined the ESA division on 1 May 2012 as the Country Programme Manager (CPM) for Rwanda. Previously Mr Coppola worked as a CPM in the Near East and North Africa Division.

Helen Gillman

Helen Gillman, Knowledge Management Officer and Coordinator of the ESA newsletter transferred to the Strategy and Knowledge Management Department as of 1 July 2012. Helen has worked in ESA for nearly four years.

Paola D’Addario

Paola D’Addario transferred to the Strategy and Knowledge Management Department as of 1 July 2012. Paola has worked in ESA for the past sixteen years.

Welcome to Périn and Lorenzo. We wish Helen and Paola “Good Luck” in their new assignments.